[Free content © AIOCS]

In this world of pointless concerns for successfulness and the lack of it, the thought of opposing a system that facilitates the acquisition of status is deeply troubling. It is easier to repress any thoughts that hinder our social success—as we chase away a nasty fly—than to exercise our function as interrogative beings. And so we never ask ourselves whether the hum of the fly makes any sense at all. The instinct of self-preservation should teach us that struggling for success and trying to maintain it are counterproductive to our wellbeing and safety. As that visionary man, Isaac Asimov, had it, “status won’t sit still under you; you have to continually fight to keep from sinking” (Prelude to Foundation). If that is the case, then why does our instinct of self-preservation fade away before the self-destructive pursuit of successfulness at all costs?

I believe that the answer rests with an innate trait of our species, namely, our curious desire and capacity to transcend ourselves, obstacles, and boundaries. Left unchecked, this trait can ruin us. History teaches that when we listen to this inner call we achieve much, but that when we pursue success at all costs we end up suicidal. Pursuing success is just one of the silly things we did, and continue to do, to keep the beast within us alive and well. Self-preservation and wisdom do no longer matter. Against this backdrop, it is increasingly unlikely that we will ever realise in full our creative potential. It is also unlikely that we will ever reach a measure of genuine heroism, including the capacity to oppose oppressive systems—especially when those systems make possible the acquisition of status, power, authority, money, and so on, which is what we desire most.

Not so is Christianity. Ever drawing upon the self-sacrifice of the Logos, true Christianity is not “the peace of a given place,” as Horia Roman Patapievici put it in Omul Recent. True Christianity builds itself heroically and wisely, against trends, against utopias, including its own utopias, against selfish drives, against the instinct of self-preservation, against conformism. Understanding that no systems—regardless of how convenient they might be, personally and socially—can guarantee a holistic and wholesome development of humankind, true Christianity adopts a critical attitude towards all social systems. Its vocation is not to canonise and worship a certain social, or political, formula or another, the right and the left. Its vocation is to foster opportune and creative imbalances, moments of crisis, times for assessment, consciously, deliberately, and wisely. True Christianity defies any tendencies towards mineralisation, refusing to grow complacent with the circular rhythms of stagnation. No wonder therefore that all who ever took Christianity seriously, not its facile and conformist versions, understood that they had to put on the yoke of a prophetic, or critical, attitude towards the social and political systems of their times, whether within or outside the ecclesial backyard. We call these people martyrs and confessors, but we do neither grasp their message nor continue their legacy.

Saint John Chrysostom (d. 407) was providentially promoted to the archdiocesan throne of Constantinople in circumstances when Christianity was becoming a steppingstone for the socially ambitious who were, then as much as today, deprived of spiritual criterion, true wisdom, moral scruples, and common sense. This was a time when the Empire clumsily and unsuccessfully attempted to put on the standards of the Good News, which it could never comprehend. The Empire Never Ended, to paraphrase Philip K. Dick. On the flip side, this was a time when the many universal churches throughout the world—which were one without needing centres of power, councils, and creeds—were remoulded in the imperial image, as a pyramid of power. This was a time when within the ecclesial microcosm golden people and wooden chalices were overnight replaced by wooden people and golden chalices.

Heroically, Chrysostom resisted the temptations inherent to his hierarchical status. He swam against the tide. He was well aware that the term which designated his ecclesial function, bishop or rather episkopos (supervisor, overseer), entailed a prophetic component. He knew that he could not supervise the ecclesial life—the wellbeing of God’s people—without spiritual discernment. Also, that he could not exercise this charism at no personal costs. But Chrysostom was a true Christian. He embraced the risks without any reservations. He transformed his episcopal palace into a shelter for the unsuccessful of the world, for the oppressed, for the poor, for the sick—all those whom the society of the indecently successful marginalised, forgot, and despised. He humbled himself, living in simplicity and tacitly opposing the tragic transformation of the church’s shepherds into imperial dignitaries, into successful people endowed with social status, money, and power. Unlike so many of the church’s princes in his time and our own, he refused to be part of the system. He refused the vain company of civil authorities, of the rich, and of the powerful. He endeavoured, in word and deed, to remind the church and the world about the things that truly matter, that is, compassion, goodness, and righteousness in Christ. And he paid the personal price. He was exiled and died in exile. In the eyes of the successful, he failed. But not in the Lord’s eyes. Nor in God’s people’s memory. We might not remember him for many things, but we remember him for having been a true Christian, a human being.

In the footsteps of the Lord whom he loved, Chrysostom was then, and so remains to this day, a peculiar bishop. In imitation of Christ himself, who was aware of his mission and pursued it to the end, Chrysostom knew why he was promoted to the episcopate and what was the price to pay in order to exercise his prophetic charism—out of love for God’s people, not in the way of the world. He was fully aware that the preacher of divine wisdom against the cunningness of the world cannot escape the only destiny awaiting those like him—the iteration, again and again, of the theodrama of the Lamb slaughtered from the foundation of the world. Humbly, he accepted it. He was not wounded by the spear of social successfulness. In turn, like many true Christians before and after him, he trampled down death by death, saying, “glory to God for all things.” For which, unworthily, we honour him.

Acknowledgment. This is the English translation, adapted, of an essay originally published in Romanian, in Bărăganul ortodox (a periodic of Diocese of Slobozia and Călăraşi) 54 (2007) 3. On this day, when we remember Saint John, I dedicate the reissue of this essay to the memory of the great shepherd, Bishop (Professor Dr) Damaschin (Damascene) Coravu of Slobozia and Călăraşi (d. 2009). I remain grateful to him as one of the only two Romanian bishops who showed both spiritual discernment and prophetic courage, publishing my work during evil days, when I was tasting the bitter bread of “brotherly love.” Memory eternal, my Father.

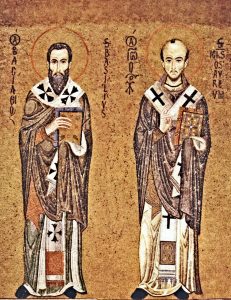

Image: Saints Basil the Great and John Chrysostom. Capella Palatina, Palermo, Italy, twelfth century. Image source

27 January 2019 © AIOCS. See also the edited collection John Chrysostom: Past, Present, Future.