(A talk offered for the annual Marian lecture of The Anglican Parish of Christ Church St Laurence, Railway Square, Sydney, 22 October 2016)

Reverend clergy, ladies and gentlemen, sisters and brothers in Christ our Lord.

Thank you for this generous invitation. It has been a great privilege to join your prayers this morning, particularly your devotion towards the Lady of Walsingham. I shall attempt to contribute to this prayerful and welcoming ambiance by introducing you to aspects pertaining to the Marian devotion of the Orthodox Church of Byzantine tradition. To illustrate Orthodox Mariology, or rather Theotokology (from St Mary’s most common attribute in Byzantine Greek, Theotokos, “the one who has given birth to God”), I have chosen the festival of the Entry of the Theotokos in the temple. Celebrated every year on 21 November, the origins of this festival are lost in the haze of history. It must have originated in the great age of Byzantine Theotokology, namely, in the sixth to the eighth century. It is then that, after the ecumenical articulation of the faith in Christ as true God incarnate of the Virgin-Mother, the Byzantines have realised that the mystery of the Lord’s incarnation can be revered both directly, in Christological festivals, and indirectly, by way of celebrations dedicated to his Mother. Although various forms of Marian devotion existed far earlier in Christian history, it is during those centuries that most Byzantine Marian festivals have been established. This is evidenced by the abundance of Theotokological hagiographies and homilies in the sixth to the eighth century. Of particular interest are the recently discovered Life of the Virgin, written by St Maximus the Confessor, possibly at the end of the sixth or in the early seventh century, and the homilies produced by reputable Byzantine preachers such as St John Damascene, St Andrew of Crete and St Germanus of Constantinople in the eighth century. Particularly the Byzantine homilies of the eighth century signal the emergence of a plethora of Marian festivals, both major and minor, of which the former are considered of equal importance to the festivals dedicated to the Lord. One such major Theotokological celebration is the Entry of the Virgin in the temple, of interest here.

In what follows I approach this festival in three stages. First of all I consider in brief the outward dimension, namely, the apocryphal information that the Virgin Lady entered in the temple of Jerusalem where she spent a number of years in the Holy of Holies, as reiterated by the Byzantine hymnography of the festival; I shall point out that the festal hymns already suggest an ecclesial interiorisation of this story. Second, I consider the same liturgical framework which, alongside maintaining the outlines of the apocryphal story, introduces a tension in that it takes the narrative as a pretext to contemplate the transformation of the Virgin into the temple of the incarnation; I identify this layer as a more profound stage in the interiorisation of the festival. Third, and finally, I show how St Symeon the New Theologian—whose repose in the Lord occurred in 1022, that is a generation before the Walsingham visions of 1061—offers a way to further interiorise the festival by suggesting the transformation of the devout after the model of the Lady’s own transformation.

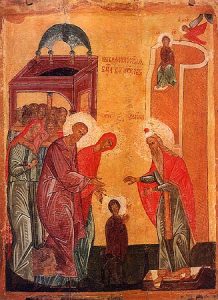

Festal icon. Image source

The first layer of interiorisation: An apocryphal narrative and its ecclesial appropriation

The hymns for the festal vespers, matins and liturgy are contained in the Menaion for November, a Byzantine liturgical book destined for the use of the ecclesiastical chanters. The hymns address various aspects of the festival, operating like an implicit catechetical introduction to the mystery of the Virgin Lady. Here is a sample from the service of matins:

The one who nourishes our life, the offspring of the just Joachim and Anna, now bodily an infant, is offered to God today in the sacred temple. She was blessed therein by the holy Zacharias. Let us all proclaim with faith that she is blessed, for she is the Mother of the Lord. (Kathisma 1)

The message of the hymn is straightforward. St Mary was dedicated to God as an infant and brought to Jerusalem, where she received the blessing of the high priest in the temple. The text recapitulates aspects of the early life of Mary as presented in the second century apocryphal, the Gospel of James. Of particular interest are sections 7 and 8, which describe how the parents of the Lady, Joachim and Anna, offered her to God at the age of three, and how, after being led to the temple in procession, she spent there, in the Holy of Holies, the next nine years of her life, until the priestly conclave decided to entrust her to the protection of Righteous Joseph. The entire festal hymnography for 21 November rehearses the same story.

That said, I have selected the above hymn given that it adds to the apocryphal narrative two new elements, namely, the recognition of Mary as Mother who nourishes our life, in other words as Mother of the Church, God’s people, and the exhortation to the latter to confess the blessedness of Mary as Mother of the Lord. These details are of crucial significance, since they already point to a festal interiorisation of the apocryphal narrative. More specifically, irrespective of the accuracy or rather inaccuracy of this account, God’s people have a certain way of appropriating the story as having to do with the relationship between Mary and the ecclesia. However, despite the obvious attempt of the Byzantine hymnographer to appropriate the narrative by interiorising it as an ecclesial event, most Orthodox take the story as true account and believe in its literal meaning. Their assumption is entertained by the synaxarion or the summary of the festival, read during matins, whose message is reproduced, with slight variations, throughout the worldwideweb. That said, deeper than the first level of interiorisation, the festal offices encode another layer of meaning.

The second layer of interiorisation: Mary as temple of the incarnation

Already in the eighth century and in a homily on this festival, St Germanus of Constantinople asserted that…

…today she enters the temple of the law at the age of three, she who alone will be dedicated and called the spotless and highest temple of the Lord… (First Homily on the Entrance, 2; see also ch. 9)

The homilist highlighted two meanings. The first layer refers to the apocryphal narrative that serves as a pretext for the festival, whereas the second one points to the transformation of Mary into a temple of God or more precisely of the Lord’s incarnation, perhaps the actual content of the festival as celebrated by the Church. The latter nuance, of interest here, finds confirmation in the very order of the festal matins. The following hymns from the office rehearse the same aspects in an expanded form.

Today the living temple of the great King comes into the temple, to prepare herself to become His divine dwelling. O peoples, be exultant. (The hymn for Glory… after the gospel reading)

And again:

The Saviour’s most pure and immaculate temple, the very precious bridal chamber and Virgin, who is the sacred treasure of the glory of God, on this day is introduced into the House of the Lord, and with herself she brings the grace of the divine Spirit. She is extolled by the Angels of God. A heavenly tabernacle is she. (Kontakion)

Both hymns highlight the two dimensions of the festival encountered in St Germanus’ homily, but in particular emphasise the mystery of the Virgin who is a living, pure and immaculate temple, ready to become a “divine dwelling” of the incarnate Lord. Thus, at a certain level of signification, the festival is about the experience of the Lady as temple—the deeper message conveyed by the outer layer of the entry story. Alongside the obviousness of the message that the two hymns convey, there are there implicit ways in which the same meaning is prompted. For instance, that the Virgin has become the temple of the incarnation is suggested by the fact that precisely during this festival the Orthodox Church begins to chant a sequence of hymns known as katabasies, which are dedicated to Christ’s birth and in which there is no reference to the Virgin’s supposed entrance in the temple. Inspired by the beginning of a Christmas homily delivered in the fourth century by St Gregory the Theologian, later transformed into hymn by St John Damascene in the eighth century, the following text is the opening item of this sequence:

Christ is born; glorify Him! Christ from heaven; go and meet Him. Christ is on earth; arise to Him. Sing to the Lord, all you who dwell on the earth; and in merry spirits, O you peoples, praise His birth, for He is glorified.

The hymn has nothing to say, not directly anyway, about the festival of the Lady’s entry in the temple. However, in being chanted in this very day it suggests that the Marian festival is the pretext of a more profound mystery—of the Virgin who has become the temple of the incarnation, by which she contributed to the event of salvation, namely, the birth of Christ. A similar reference to the Lady’s transformation into a divine temple is suggested by one of the readings prescribed for the liturgy, from Hebrews 9:1-7, which offers a description of the sacred items in the Old Testament tabernacle. Granted, taken at face value this pericope has nothing to say about the Marian festival. Nevertheless, when connected, in the sermon, with the other reading, from Luke 10:38-42, 11:27-28, the message becomes transparent: St Mary, the one praised in the last of the Lukan passages, is the tabernacle of the incarnation.

The above examples provide abundant proof that the festival celebrates Mary the Temple, not Mary’s entry in the temple. The captivating apocryphal narrative of the Lady’s infancy is resignified within the framework of the festival, becoming the parable by which another message is proclaimed, namely, the Lady’s divine transformation in preparation for the incarnation and as an outcome of the incarnation. On this note I must turn to the third layer of interiorisation, by drawing on an external source to the liturgical rites—St Symeon the New Theologian’s First Ethical Discourse.

The third layer of interiorisation: The personal dimension

The main hymn of the festival, known as apolytikion, already alludes to this third level of interiorisation:

Today is the beginning of God’s good favour and the proclamation of humanity’s salvation. The Virgin is presented openly in the temple of God and she announces Christ to all. Let us, then, with a great voice cry aloud to her: “Rejoice, you are the fulfilment of the Creator’s dispensation.”

The hymn connects the Marian festival and the mystery of Christ, in that it has the Virgin announcing to the world the arrival of the Lord. Furthermore, it affirms that—“today”—we are given a foretaste of God’s favour and that our salvation is inaugurated. The association of these elements is not explicit, but neither is it difficult to pinpoint. The festival of the Virgin, which celebrates her transformation in the temple of the incarnation, both prefigures Christmas and reveals our destiny, which is intrinsically linked with both the mystery of Mary and the salvation which Christ wrought. It is with this latter nuance that I concern myself in what follows.

Before I turn to St Symeon’s interiorised Theotokology, it is noteworthy that the views he developed around the turn of the first millennium built on at least a couple of traditional antecedents. The first relevant occurrence of the topic of our transformation is the classical Pauline passage in Galatians 4:19, where one finds that the apostle was “again in the pains of childbirth until Christ is formed” in the readers. The fact that he referred here to an experience of Christification—as a fourteenth century Byzantine mystic, St Nicholas Cabasilas, calls it—is inescapable. Thus, St Paul talked about a mystical intimacy with Christ, an experience which consists in the dwelling of the Lord in the believer and the latter’s reconfiguration in the image of the Lord. Later, in the first half of the seventh century, St Maximus the Confessor affirmed, in his Book of Difficulties or the Ambigua, ch. 7.23 (ed. Constas), that “the Logos of God, who is God, wills always and in all things to accomplish the mystery of His embodiment.” Here, the Pauline image of Christ taking shape within the believers, particularly the nuance of his indwelling, is straightforward likened to an incarnation or embodiment. According to St Maximus, the Logos of God wishes to put on the flesh of all of his creation, human and cosmic. At this juncture, however, St Maximus’ incarnational spirituality does not make plain what is the outcome of this universal embodiment of the Lord, “always and in all things.” What matters is the proposal of a repeated incarnation of God’s Word on a personal, particularised level. This is where St Symeon intervened decisively, in that he considered the content of Christification through the lens of the Theotokos. For him, and in short, the Christian experience replicates on a personal scale the experience of the Virgin who received the Lord within her womb and has become a temple of the incarnation, a temple of God. Here is what St Symeon had to say:

God, the Son of God, entered into the womb of the all-holy Theotokos and, taking flesh from her and becoming man, was born … perfect God and perfect man. … All of us who believe in the same Son of God and Son of the ever-virgin Theotokos, Mary, in believing, receive the word concerning Him faithfully in our hearts. When we confess him with our mouths and repent our former lawlessness from the depths of our souls, then immediately—just as God, the Word of the Father, entered into the Virgin’s womb—even so do we receive the Word in us, as a kind of seed, while are being taught the faith. … We do not, of course, conceive Him bodily, as did the Virgin Theotokos, but in a way which is at once spiritual and substantial. … when we believe wholeheartedly and fervently repent, we conceive the Word of God in our hearts, like the Virgin… (First Ethical Discourse, 10)

The above passage does not refer to the festival under consideration, but the Symeonian vision appears to have continued the process of interiorisation begun with the ecclesial appropriation of the story in Gospel of James and more so the interpretation of that story as signifying the transformation of Mary in the temple of the incarnation. St Symeon contemplated the mystery of the Theotokos as paradigmatic for the Christian experience and consequently used this paradigm as a key to unlock the mystery of the Christian experience. For him, and keeping the proportions, all the members of God’s people are called to achieve what one could call a theotokological state. Like Mary, all believers are called to interiorise the Word, the Logos of God, through faith and conversion, so becoming pregnant with God, as it were. In this light, the relationship between each believer and Christ is analogous to the relationship between the Lady and her Son.

So interpreted, mystagogically (as the Byzantines would say), the Orthodox festival of the Lady’s entry in the temple occasions a meditation at once on Mary’s mystery and the overall Christian experience, in the same light of the incarnation. The apocryphal story of the Lady’s entry in the temple becomes the story of her transformation into the temple of the incarnation. In turn, when perceived through the lens of Mary’s experience, our own life in Christ is, to say with St Symeon, theotokological. And so, when we contemplate the mystery of Mary the Theotokos, the true temple of the Lord’s incarnation, we are given an opportunity to catch a glimpse of our own spiritual journey.

Acknowledgment

Originally published on academia.edu

21 November 2019 © AIOCS