Theophany and Its Ethical Trace: Christianity According to Father Nicolae Steinhardt

Theophany and Its Ethical Trace: Christianity According to Father Nicolae Steinhardt

(This text represents the author’s own English translation of Bogdan G. Bucur, “Die Theophanie und ihre ethische Spur: Christsein nach Vater Nicolae Steinhardt,” Ostkirchliche Studien 71.2 (2022): 315-330.)

Among the many witnesses of Christ that flourished in Romania, I would like to recall the monk of Rohia, Nicolae Steinhardt, an exceptional example of a believer and man of culture, who had a special insight into the immense richness of the treasure common to the Christian Churches. (Pope John Paul II, Sunday, May 9, 1999)[1]

For many Romanians who discovered his writings soon after the 1989 fall of Communism, Fr Nicolae Steinhardt embodied and expressed the Gospel of Jesus Christ in a way that made Orthodoxy credible in spite of the many flaws of the Church as an institution. Steinhardt remains a spiritual mentor for anyone seeking to re-learn the faith and to share its joy and beauty with the world.

A sui generis Orthodox Creed

In a short text composed in the late 1980s at the Rohia Monastery, in Northern Romania, and intended to be included in a collection of his sermons—but, of course, without any hope of ever seeing such a book in print—the monk Nicolae articulated the main tenets of his Christian faith in a sui generis “Orthodox Creed.” Allow me to quote from it at some length:

I believe in One Lord Jesus Christ who, without change, out of mercy and love for us, has taken on flesh in order to comfort us, to come to our help and to gift us the sense of dignity and nobility; who for us valiantly ascended the cross—since he was not only kind, meek, and humble of heart, but, above all, courageous; […] who loves the righteous and is gracious towards sinners, but reserves a strong and undeniable affection for those who are unafraid, even if they be weighed down by heavy burdens of the past; who does not forget that he, too, was a man dwelling on earth, where he received his scars and acquired a special disgust for informers, fearsome functionaries, and bureaucracy.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, who blows whenever and wherever he wills, scandalizing and befuddling pharisees, angelists, and church zealots; […] and who does not appreciate unctuous flattery, pious prayer posturing, and showy morality.

Our faith, I am convinced, […] does not go well with a strictly organizational understanding of the Church as a legal and cold, and ultimately inquisitorial, organization: frowning faces and stiff necks; neither does it go well with stupidly-seraphic gigglings, or disorderliness, or restiveness. It does not allow itself to be defeated and convinced by all the violence, pain, injustice, and cruelty of the world; it believes in God in an adversative way: against these things, despite and in spite of them, although they do, alas, exist in abundance.

I confess one baptism unto forgiveness of sins and unto liberation from the yoke of prejudice, pettiness, and small-mindedness, and unto adopting Christ-like reactions in the rush of everyday life, with its deeds and events. […][2]

Those who met this monk in literary circles, during the 1980s—his abbot having given him the blessing to continue his work as an essayist and literary critic—sensed something Christ-like, utterly “other,” and utterly endearing about him. As one of them writes, “Steinhardt was among all like a saint. Like Saint Nicholas: kind, generous, wise, prodigal with himself, protective of those who needed to be protected.”[3]

But this is not how it all began. The elderly Monk Nicolae was once, as a close friend described him, “a young bourgeois intellectual, coming from a very wealthy Jewish family,” who “could afford leading a luxurious, refined, life, free of any and all obligations.” Hyper-educated, a voracious reader, first book published at age 22; but also quite “cynical, individualistic, critical, hedonistic, etc.”; “a small, devilish provocateur … a Voltairean spirit, ironic and highly spiritual; I cannot say that nothing was sacred to him, but he exuded irreverence in his conduct.[4]

What had happened, what had changed him? Life, of course, with its ups and downs. More specifically: prison, political incarceration. In the secret interviews he gave Nicolae Băciuț between 1986 and 1988, Steinhardt is proud to introduce himself as “an ex-bandit and steady client of the Secret Police”; “old prisoner and client of the Securitate,” a protester against “the official puritanism and victorious stupidity.”[5] Rather than betray his friends and serve as the tool of an unjust and absurd prosecution, he had preferred to join them in prison—and, in fact, declared loudly that it was an honor to do so.

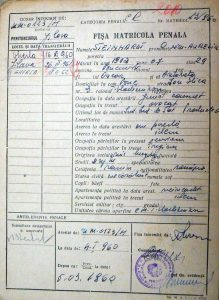

Steinhardt and his father spied by the political police (photo supplied by the author)

It is then, after his arrest in 1959, that he was granted what he himself called a certain “prefiguration of monastic Hesychasm.” This occurred, certainly, in his secret baptism in the cell, as we shall see; and certainly in a (quasi?)mystical experience of Christ as light and intense joy, an experience for which words proved powerless—but which constituted, nevertheless, the hyper-concentrated core generating the over 500 pages of his Journal of Joy.[6] But such a prefiguration also occurred in the paradoxical encounter of his fellow inmates: “in the prisons through which I have passed I encountered quite a few truly true saints.”[7] It is there, in the belly of a hellish laboratory of dehumanization, that he found himself among fellow inmates who all remain “kind and joyous as only folks in prisons can be—a foreshadowing of monastic hesychia or of heavenly bliss.”[8]

Steinhardt’s retrospective evaluation of how prison changed him speaks for itself:

I went into prison blind (with vague flashes of light, but not pertaining to reality—internal, the self-created flashes of the darkness, which split the darkness without dispelling it); I leave with my eyes open. I went in spoiled, pampered; I leave healed of airs, whims, vanities. I went in discontented; I leave knowing happiness. I went in nervous, quick to anger, sensitive to trivialities; I leave impassive. The sun and life spoke little to me; now I know how to taste the slice of bread, no matter how tiny. I leave admiring courage, dignity, honor, heroism most of all. I leave having made my peace with those I wronged, with my friends and enemies, even with myself.[9]

Hell, the Locus of Theophany

The document of Steinhardt’s arrest (photo supplied by the author)

Although the prisoners’ faith, supported by divine grace, did, indeed, convert prison into a laboratory of holiness—just as, in the words of a Byzantine hymn, the zeal of the three youths and the presence of the “mystical angel,” Christ, transformed the fiery furnace into a heavenly church—Steinhardt does not mince words in depicting the horrific reality of his imprisonment:

Cell 34 is a kind of long and dark tunnel. It has many of the powerful elements of a nightmare. It’s a cave, it’s a canal, it’s a subterranean intestine, cold and deeply hostile, it’s a barren mine, it’s an extinct volcano’s crater, it’s a pretty successful image of a discolored hell.[10]

It was sad and ugly in cell number 25 too, in section 2. … Soot covers everything in a thick, greasy layer of slimy blackness, continuously expanding, adhesive. We are shaking with cold, we feel overwhelmed by dirt—and we are hungry. … We have no more water. The bucket is full. Strangely, the frost, instead of neutralizing the smell of feces, makes it worse. We wait for the arrival of the bread like caged animals whose feeding is at the mercy of a forgetful master. The lump is frozen and is made of cornmeal that has only been baked, not boiled.[11]

And yet, in these cells, “designed only to lead people to denunciation and filth, to collapse and madness,” he met true heroes who “twenty-four hours a day retained their dignity,” and “recognized what goodness, decency, heroism, dignity are.”[12] Most importantly, he writes, “in this almost fancifully unreal and sinister place, I was to know the happiest days of my life.”[13]

Baptism, Theophany, and the Experience of Light

It is there, on March 15, 1960, that the hieromonk Mina (Dobzeu) poured wormy water from a chipped kettle and baptized him in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit—with the expectation that, should Steinhardt somehow survive his twelve-year prison sentence (a rather unlikely scenario for a frail man who would be subjected to savage beatings and torture)—he should later seek to be chrismated.

Two of the detainees, accomplices, pass in front of the peephole to block it. The warden could come and look at any moment, but now that the cells are taken on walks or brought back by turns, it’s unlikely. Hastily – but with that priestly skill where haste doesn’t hamper the clarity of the diction – Father Mina utters the necessary words, marks me with the sign of the cross, pours all the contents of the kettle on my head and shoulders (the cup is a kind of chipped kettle) and baptizes me in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. …I am born again, out of wormy water and a swift spirit. We venture back to the bed of one of the Greek-Catholic priests, close to the bucket and vat … and there I recite the (Orthodox) Creed, as we had established. I renew the promise not to forget that I was baptized under the seal of ecumenism. Done. Under such circumstances, baptism is perfectly valid without either the immersion or the chrismation. (If I survive prison, I am to present myself for chrismation to a priest whose name Father Mina gives me.)[14]

Baptism propels him in a state of near-mystical ecstasy, which he reports in words that the masses of “cradle Orthodox” taking their sacramental initiation into the Body of Christ for granted might find surprising:

Whoever was christened as a small child has no way of knowing and cannot imagine what baptism means. Above me dawn ever more frequent assaults of joy. One might say that each time, the besiegers climb higher and hit with greater relish and precision. So it’s true: it’s true that baptism is a holy mystery, and that holy mysteries exist. Otherwise this happiness that surrounds me, fills me, clothes me, overcomes me wouldn’t be so unimaginably wonderful and whole. Peace. And absolute indifference. Toward everything. And a sweetness. In my mouth, in my veins, in my muscles. Also a resignation, the feeling that I could do anything, the impulse to forgive everyone, a tolerant smile that spreads everywhere, not limited to the lips. And a sort of layer of tender air all around, an atmosphere similar to that found in some childhood books. A sense of absolute certainty. A mescaline-like merging into everything, and a perfect departure into clarity. A hand that reaches out to me, and a complicity with barely discernible wisdoms. And the newness: new, I’m a new man. From whence so much freshness and newness? Revelation (21:5) is proven true: Behold, I make all things new. And Paul also: If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; the old things have passed away; behold, all things have been made new (2 Cor 5.17). New, but ineffable. I can’t find words except for trivial, stale ones, those I always use.[15]

Under the dating of May 1963, Steinhardt also documents (after having shared it, cautiously, with a saintly hieromonk by name of Haralambie) a similarly overwhelming experience that had occurred some eighteen months earlier. “I call it as a dream,” he writes at one point, “because I dare not call it something else”; in recounting it, however, he refers to it as “a miraculous dream, a vision”:

The following night I fall asleep dead tired. And then, exactly on that night, I’m gifted with a miraculous dream, a vision. I don’t see Christ the Lord incarnate, only a huge light—white and bright—and I feel unspeakably happy. The light surrounds me on all sides. It’s total joy, and it does away with everything. I’m bathed in blinding light; I float in light; I am in light and I exult. I know that it’ll last forever; it’s a perpetuum immobile. “I am,” the light says to me, not through words but through the transmission of thought. “I am”: and I understand through my intellect and by the means of feeling—I understand that it’s the Lord and that I’m within the light of Tabor, that I don’t merely see it but also dwell in its midst. Over and above everything I’m happy, happy, happy. And I know that I am, and I say it to myself. And it’s as if the light is brighter than light and it’s as if it speaks and tells me who it is. It seems to me that the dream lasted long, very long. The joy not only lasts a long time but also constantly increases. If evil has no bottom, then goodness has no ceiling. The circle of light grows ever wider, and the joy, after it has enveloped me silkily, suddenly changes its tactics, becomes firm, throws itself, collapses upon me like avalanches that—anti-gravitationally—lift me up. Then, again, it proceeds otherwise: tenderly, it cradles me, and in the end, bluntly, it replaces me. I no longer am. No, I am, but so strong that I no longer recognize myself.[16]

The bold statement, “I am within the light of Tabor,” is perhaps especially noteworthy. It has been argued that Steinhardt’s luminous experience, which leaves him in a state of being both himself and other-than-himself (cf. Gal 2:20), fits squarely within the venerable tradition of the experience of God, as illustrated by Symeon the New Theologian (949–1022), Seraphim of Sarov (1759–1833), Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov) (1896–1993).[17] It should be also noted, however, that this mystical experience had left an unmistakable ethical trace in Steinhardt’s Journal and Creed, crystallized into a number of memorable, clearly articulated ethical mandates that offer us much needed orientation today.

The Ethical Trace of Theophany: Joy and Kindness

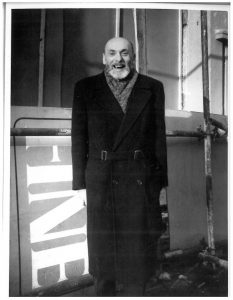

Steinhardt laughing (photo supplied by the author)

As one can easily gather from the very title of his magnum opus, Steinhardt counts joy as an important marker of genuine spirituality.

In order to distinguish the Christian from the caricature or imitation, there’s no procedure more certain than investigating whether the aspirant is cheerful and content. If the person is intolerant or sullen or agitated or sad or upset, he’s not a Christian, no matter how faithful to virtue… The Christian is free, hence happy.[18]

Joy is, as we have seen, part of the description of the ecstatic state associated with baptism: “Over and above everything I’m happy, happy, happy. … The joy not only lasts a long time but also constantly increases.” It erupts again (and with the same associations with the Christian ascetic-mystical tradition: hesychasm, uncreated energies) in Steinhardt’s narration of the grace-filled forgiveness and reconciliation with a former member of the antisemitic Iron Guard:

Waves of joy wash over us, flow, flood us, overwhelm us. I ask Sandu … whether he sees on my lips the smile that I spy on his: that of hesychasm having its origin in the uncreated energies. For in the tight nook there was room alongside us for Gregory Palamas with St Seraphim and Nicholas Motovilov after him.[19]

Joy is cultivated as part of an everyday ethics of thoughtfulness, kindness, benevolence, and courage—a Christian formula that excludes any self-righteous, morose, pseudo-religious zealotry:

Fundamentalist fanaticism of any kind is repugnant and feels daft to me…. The monk zealously employing fundamentalist fanaticism is only masquerading as a Christian, and is an Orthodox estranged from the faith he is supposedly professing and witnessing. Our faith has always been known for its steadfastness but also for its distaste towards anything that is not grounded in Christian kindness and in our forefathers’ discernment.[20]

I think that the sins committed in all the brothels of Paris, Hamburg, and Singapore, in all the places of perdition of all the ports and metropolises of the world, … do not cry more dissonantly and woefully to the heavens than the insults, sudden arguments, and gratuitous insults uttered with vitriolic hatred by the quarrelsome and morose.[21]

The Ethical Trace of Theophany: Courage

Steinhardt’s real-life model and embodiment of virtue was his elderly father. The mystical experience confirmed, renewed, and intensified the courage, moral clarity, and prudence that Steinhardt’s father, Oscar, had already imprinted upon his son chiefly by personal example. Following the initial “invitation” to sign a declaration incriminating his friends as enemies of the State—the accusation: they had procured, read, and discussed novels by Mircea Eliade and Emil Cioran’s The Temptation to Exist!—Steinhardt had asked for a few days of reflection and had returned home. His father met him with a stern rebuke:

Why’d you come home, you fool? You gave them the impression that you’re hesitating, that there’s a possibility you might betray your friends. In business, when you say ‘Let me think,’ it means you’ve accepted already. But you must, under no circumstances, accept to be a witness for the prosecution! … Come on, stop dawdling: you must go to prison. I am heartbroken, but there is no other way.[22]

On the day of the arrest, it is again the elderly Oscar Steinhardt who shines:

My heart is heavy. Dad however—in his pijamas, tiny, chubby, joyous—is full of smiles and dispenses last pieces of advice, like a coach before the bout […]: they told you to not let me die like a dog? Well, if that’s how it is, I tell you what: I’m just not going to die! I’ll wait for you. And you—now listen to me: don’t you embarrass me; don’t be a fearful Jew; don’t shit your pants!” He kisses me emphatically, leads me to the door, stands up straight and salutes me military style: Go, he says.[23]

When Steinhardt writes his Journal in the 1970s and his Creed in the late 1980s, we see clearly how this lived experience has opened to him the Scriptures and an understanding of Christ from which we, today, have much to learn. You recall, in the Creed, that Christ is described as “not only kind, meek, and humble of heart, but, above all, courageous” and that “he reserves a strong and undeniable affection for those who are unafraid”; and the Journal of Joy insists that “Christianity isn’t sheepish” and is, in fact, “a religion of courage.” Several times Steinhardt draws our attention to the many and well-known biblical injunctions to “take heart,” to not be afraid, to not fear, as well as to a much less remembered detail in the book of Revelation (Rev 21:8): “Among those consigned to the fiery lake, who is it that comes first? The cowardly!”[24]

Courage is not only to be proven in extreme situations; Steinhardt’s recipe for daily life calls for the following: “Ask. Demand. Knock. Dare. Don’t be afraid. Don’t be frightened. Persevere. Charge. Be awake. Be of sound mind. So many exhortations abundantly showing that it doesn’t behoove us to be stupid!”[25]

With this, we discover another facet of “Christianity according to Steinhardt”: Intelligence.

The Ethical Trace of Theophany: “It is not meet and right for the Bride of God to be stupid!”

In a private letter from 1972, Steinhardt writes:

People take Christ as a moralizing pastor, and Christianity, too, as a vague teaching rendered into the curricula of the schools of cowardness, silliness, and pharisaism. … I view coward imbecility as being from the devil, and I refuse to take the pious style [stilul cuvios] as a sine qua non condition of Christianity.[26]

This is a theme picked up in the Journal:

It sets my teeth on edge when I see how Christianity is confused with stupidity, with a kind of cowardly and stupid piety, a religious knick-knack … Nowhere and never did Christ ask us to be stupid. He calls us to be good, tender, honest, and humble-hearted, but not idiots … The Lord loves purity, not imbecility. … God, among other things, commands us to be intelligent. For the one who is blessed with the gift of understanding, stupidity—at least from a certain point onwards—is a sin: a sin of weakness and of laziness, of not using of one’s talent.[27]

For Steinhardt, “intelligence” and “stupidity” are used primarily as indicators of moral soundness. When he writes, quoting St Bernard of Clairvaux, that “it is not appropriate for the Bride of God to be stupid,”[28] what he has in mind is a sort of willful (and therefore culpable) intellectual and moral self-amputation:

No one is obligated to invent gunpowder or to discover quantum theory. On the other hand, though, an elementary smartness is a duty. … Ignorance, idiotization, passing blindly or indifferently through life and through things, are all from the devil.[29]

Certainly, Steinhardt is speaking from a specific historical vantage-point: the wave of thousands upon thousands of political prisoners released in 1964, and the thousands of interactions between these confessors of freedom and the general population who had been terrorized into submitting to, and normalizing, Communist rule. Beyond that historical context, however, when today’s Christians succumb to the temptation of obfuscating, minimizing, relativizing, or even justifying the atrocities taking place within the Orthodox world, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, by invoking the highly complex geopolitical and ideological realities, the fog of war, the inherent ambiguities of Church-State relations, etc, the following statement retains its full force:

“I didn’t know”—the answer of those who are told about torture, about concentration camps, about prisons, about the [forced] admission of accusations, about political internment in mental asylums—“I didn’t know” just won’t cut it; it is not a valid excuse.[30]

The “intelligence” or clear-sightedness that Steinhardt sees as mandatory for Christians also includes a certain sobriety, a refusal to be taken in by seeming benign (or even positive) disguises of evil. What can be objectionable, for instance, when a notable (and, of course, regime-friendly) university professor delivers magnificent lectures on 19th-century Romanian poetry? Or when Theology journals publish robust studies detailing the Catholic crimes and abuses in 18th-century Transylvania? Or when the Communist authorities pass Decree 770 / 1967 penalizing abortion? Shouldn’t one bracket out the political issues of the day and simply recognize what is correct, accurate, and morally good?

Steinhardt cannot agree with priests “who glorify the edicts of the police in regard to haircuts, girls’ skirts, etc” and “who make haste with fiery words of praise in approving the moral measures taken by some totalitarian governments (the abolishing of prostitution, the prohibition of abortion, complicating divorce) … [They] have in mind, I believe, more the letter and severities rather than the spirit in which such measures are grounded.” One should not, he writes, strain the gnat and swallow the camel (Mat 23:24), see the mote and conceal the beam (Mat 7:3-5); tithe cumin and dill (Mat 23:23); or forget “the Terror and the Lie” cast upon the nation, and conveniently leave behind the fact that freedom is an essential ingredient in everything truly good and truly virtuous because “the Spirit can’t blow except where there is freedom and where virtue issues from free will.”[31]

Christians must always remember that the “true” truth is the truth that is relevant—which is usually the truth that a dictatorship will not allow. Therefore, giving lectures at the University— “that Goethe wrote Poetry and Truth, that Voltaire died in 1778, or that Balzac, ladies and gentlemen, is a Romantic realist”[32]—while the professor’s former colleagues are being tortured in the Gulag; or publishing respectable studies about the historical ills of Uniatism in Transylvania, while the entire episcopacy of the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church was perishing in prison—Steinhardt finds all of this frivolous, ridiculous, and lacking in basic Christian and human decency. And “without the slightest hint of malice or disrespect, but also without the customary beating around the bush,”[33] he puts the matter clearly:

When people are being sawn in two right next to you, announcing that “two and two is four” means that you must scream at the top of your lungs: it is an injustice crying out to heaven that people should be sawn in two![34]

Seeing Like the Samaritan, Becoming “Impostors of the Good”

Indifference—or, in Steinhardt’s blunt verdict, “willful blindness,” “cowardly imbecility”—is from the devil. Like the Good Samaritan, Steinhardt notes, who “wasn’t merely good, but also attentive: he knew how to see,”[35] God’s people must also be clear-sighted, attentive, vigilant.

Otherwise, why would the Lord tell people, “This is your hour”; and why would he exhort them to see with their eyes, to hear with their ears, and to understand with their hearts.[36]

Note what Steinhardt does with this line, which, in the Gospel of Luke (22:53), the Lord spoke to those who had come to arrest him —“this is your hour and the power of darkness”: he applies it to Christians, and to their duty of seizing the God-given opportunity to meet Him here and now by meeting and loving one’s neighbor. Indeed, why cede the recognition of the “hour” of success to evil? Shouldn’t the sons of the light be more effective, in their faith, than the sons of darkness are in their commitment to evil?

Recognizing “this our hour,” being vigilant in seeking Christ in our suffering neighbor, and “adopting Christ-like reactions in the rush of everyday life, with its deeds and events” is a matter of perpetual striving. As a matter of fact, Steinhardt ends his Orthodox Creed with one of his favorite verses: Mark 9:24, “I believe, Lord! Help my unbelief.”

He is also keen on deflating any dreamy talk of heroic striving forward on the path of holiness, ascending from glory to glory, and to, instead, emphasize the blessing of modest, even ridiculously modest, gains:

The saints are the limit. After them come the heroes, and then those of noble character; and after them come limping along—somewhat ridiculous, panting a little—those who dare to do the good.

We’re not clean children, we’re not saints. But—come on!—neither are we some kind of scoundrels, some kind of salauds. Not saints, certainly. But maybe the next best thing: that is, impostors of the good.[37]

A Generous Assessment of the World

Steinhardt’s immense culture reminds one of early Christian authors such as Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, or Gregory of Nyssa. They were advocates of a high, optimistic anthropology, emphasizing the innate Christ-orientation of all humankind, since each one is made in the image of the divine Word and Image, Christ; and they also marveled at the overly generous presence of the Logos not only in the Israel of the patriarchs and prophets, and, fully, in the Church, but also, as “seminal Logos” with anyone, anytime, anywhere who sought knowledge, justice, and beauty. Like them, Steinhardt is remarkable in his generous assessment of the world outside the Church. He values any shred, however tiny, any echo, however faint, of the Gospel. Thus, he can make pronouncements such as these:

Listening in stereo to the entire rock-pop opera Jesus Christ Superstar, by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Mary Magdalene’s character – text, role, voice, interpretation – is extraordinary. … She sees Christ, suspects his immense pain, foresees his tragic fate, understands that it has to do with a sacrifice. And she only knows one other thing: to console the persecuted innocent. In the text of the rock-pop opera, which paraphrases the gospel text, she says to him: don’t think about us, don’t think any more, rest in peace, all shall be well, let the earth spin by itself tonight. She dares lead him on with warm words and lie to Christ! The mother’s love for her child: all shall be well, sleep, don’t worry, don’t you bother yourself with us. … Mary Magdalene’s example – and how the rock-pop opera brings her to life! – means for us that we don’t have to slip into abstractions and generalization, thinking of the poor who aren’t present and who constitute a simple mental category (or, put another way, an alibi); that it becomes us to comfort Christ, meaning the present one, who suffers before us and waits, now, here, for our compassion (co-passion). Ah! It’s not bad to want the good of humankind and of the poor and of the working class, but it’s easy; it’s harder to carry the paralyzed detainee (who might be faking it) on your shoulder to the bucket; to hand the bedpan to this operated man who can’t get out of bed (and who might be exaggerating a bit), to endure General Constantinescu-Țăranu’s snores[38] without waking him from his sleep and demanding threateningly that he lie on his side (it wouldn’t be impossible for him, really); to care for this jerk who urinates in the canteen … We should help this person through deeds, now, as we can, if only with a kind word, a consolation, an attentive ear, a gift, a rub down, a walk to the drugstore, this person, not those who aren’t present, not clean abstractions and categories, faraway, discreet and full of qualities, which don’t snore loudly and don’t urinate in the canteen. To help our neighbor full of wounds and sins, of ugly and reeking wounds, of disgusting and petty sins, a fault finder and full of manias, insolent, thankless, ungrateful, filthy, stubborn, pretentious, for whom nothing is good enough and who answers to the good done him, if not with swear-words, at least with digs, ironies and resentments. … I think three creatures sprinkled the cross of Christ with a little dew: Mary Magdalene, the good thief and, before, Nicodemus, who showed the Lord that the good seed would be able to yield good fruit even in the compact ranks of stubborn duplicity. (Three creatures – and Mary’s tears).

Conclusions

A dramatic loss of credibility will likely confront the Orthodox Church in the coming decade. Leaving aside the rapid secularization of Christian societies that are succumbing to the commodification and commercialization of human existence, the most potent seeds of disillusionment and apostasy, however, are being sawn right now by the behavior of the Church hierarchy during the current war in Ukraine—an explosive metastasis of many cancers that we have allowed to fester in the ecclesial body for many decades and centuries of flirting with Empire and becoming addicted to the power it grants.[39] We see clearly today that we, Orthodox Christians, haven’t yet learned the basics: do not lie, do not steal, do not kill, and do not take the Lord’s name in vain by claiming to kill in defense of the faith. Too many seem to have learned their Orthodoxy at the feet of the Grand Inquisitor, and too many are being catechized by his propagandists.

Father Nicolae Steinhardt’s embodiment and articulation of the Gospel reminds us that there can be no genuine “mysticism” (by which I mean, simply, our hidden life in Christ) without a robust ethical counterpart. As Christians, we are called to live not by lies—whether lies we tell ourselves, lies we accept, lies we tell others; to remember that ours is a faith that demands and empowers us to be courageous; to cultivate kindness, patience, and a sense of humor; to deepen our commitment to Christ and, at the same time, practice an intelligent, civil, and generous assessment of the world around us. All of this constitutes a potent antidote to the pompous evil, ugliness and stupidity of today’s orthodox pseudomorphosis, and a strong impulse to allow God to do his liturgy in us, to give us the joy of being, for now, “impostors of the good,” and to save us despite ourselves.

Notes:

[1] https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/de/angelus/1999/documents/hf_jp-ii_reg_19990509_bucarest.html

[2] Nicolae Steinhardt, “Orthodox Creed,” in Dăruind vei dobândi. Cuvinte de credință (Editura Mânăstirii Rohia, 2006), 353-55.

[3] Nicolae Steinhardt, Între lumi: Dialoguri cu Nicolae Băciuț (Cluj: Dacia, 2006), 147.

[4] From an interview with Alexandru Paleologu, which Băciuț conducted in 1992 (Între lumi, 127-128).

[5] Băciuț, Între lumi, 36, 46, 56.

[6] In a written declaration given on the very day that the Securitate had confiscated the manuscript of the Journal of Joy (December 14, 1972), Steinhardt describes his work as follows: “it represents an intimate journal written by me, at my home, during 1970-1971, in which I have striven to give a detailed account of my religious conversion, that is, my move from Judaism to Christianity. I felt the need to clarify to myself this profound spiritual process” (ACNSAS, Fond informativ, Dosar nr. 207, vol. IV, ff. 289; apud George Ardeleanu, N. Steinhardt și paradoxurile libertății (București: Humanitas, 2009), 176.

[7] Băciuț, Între lumi, 42.

[8] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii (Iași: Polirom, 2008), 185.

[9] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 514-515.

[10] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 82.

[11] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 184-185.

[12] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 118, 163.

[13] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 82.

[14] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 169. Upon the general amnesty of political prisoners, the newly released Nicolae Steinhardt was indeed chrismated on September 12, 1964, at the Schitu Darvari church in Bucharest, accompanied by his godfather from prison, Emanoil Vidrașcu, and his wife Rodica. Year after year he would write the Vidrașcus on the anniversary of his baptism. For instance, in 1988, he sends the following: “For March 15th. My dear godparents and friends, Thinking of March 15th, 1960 with love, gratitude, and friendship; as well as of September 12, 1964, I pray fervently for your health and blessing. With all my heart, with all my soul, with all my mind in the Lord, Yours, Nicu.” Text from N. Steinhardt, Corespondență. Editie ingrijita, studiu introductiv, note, referinte critice si indici de George Ardeleanu. Repere biobibliografice de Virgil Bulat (Mânăstirea Rohia: Polirom, 2021), 281-282.

[15] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 170.

[16] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 186–87.

[17] Paul Ladouceur, “The Experience of God as Light in the Orthodox Tradition,” Journal of Pentecostal Theology 28 (2019): 165-185.

[18] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 569.

[19] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 127.

[20] Steinhardt, “Reflecții călugărești” [“Reflections on Monasticism”], in Dăruind vei dobândi, 356-370, at 361.

[21] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 344.

[22] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 70, 72.

[23] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 73.

[24] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 58, 202.

[25] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 438.

[26] Letter to Virgil Ierunca (October 31, 1972), in N. Steinhardt, Corespondență. Editie ingrijită, studiu introductiv, note, referințe critice și indici de George Ardeleanu. Repere biobibliografice de Virgil Bulat (Mânăstirea Rohia: Polirom, 2021), 637.

[27] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 62, 63.

[28] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 559. See Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the Song of Songs 69.2: Non decet sponsam Verbi esse stultam.

[29] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 117.

[30] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 117.

[31] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 537.

[32] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 68.

[33] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 69.

[34] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 68.

[35] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 117.

[36] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 117.

[37] Steinhardt, Jurnalul fericirii, 195.

[38] Cf. Jurnalul fericirii, 185: “the greatest snorer of all times and all prisons. The sound he used to produce was so triumphant, irresistible and ferocious that there was never any question of being able to sleep in the same room as him”

[39] See “A Time of Reckoning for the Church: Theological Reflections on the Tragedy of the War in Ukraine,” St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 66.1–2 (2022): 5–10, at 8-9: “In sum, the prophetic and pastoral failure of the Moscow Patriarchate is the acute manifestation of deep-seated ills that plague much of the Orthodox world. Nationalist tendencies reflect a crisis of synodality in the Orthodox Church worldwide. But the Church also suffers from a crisis of catechesis and from the dilution of its ascetical and ethical character: how else can political and military passions and simplistic East-West binaries so overwhelm the mind of self-proclaimed Orthodox Christians, that spilling the blood of another people (let alone of fellow Orthodox) be deemed acceptable? And the Church suffers from a crisis of leadership: leaders of the various local Orthodox churches has repeatedly shown a predilection for accommodating rich, powerful, corrupt political strongmen by forgetting its traditional critique of wealth and power, muting its prophetic voice, and narrowing its eschatological and catholic horizons to a myopic focus on history and nationhood. … On none of the above-mentioned points can any hierarch, theologian, or local Church claim the moral high ground or the right to lecture others. The unpleasant truth is that most local Churches have allowed these ailments to poison the life of Orthodoxy for decades and centuries, thus creating the ideological premises, and shaping the ethos of the actors involved in today’s war. There are, certainly, degrees of complicity with error and evil. And it is true that elevating blood, language, and national history over Baptism and liturgical and ethical formation does not always result in widespread violence and death—but the current war reminds us how easily it can. … Nevertheless, we find it important to state, speaking as Orthodox Christians, that we should not fancy ourselves innocent of complicity with the very ideas and practices that are fueling the war in Ukraine, and we should not pretend that such complicities are only a thing of the past. We have much to repent of, and much work to do.”

A Note on the Author: Father Bogdan Bucur is an Associate Professor of Patristics at St Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary. After studying at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology in Bucharest (1994-1999), he left for the USA, where he earned his MA (2002) and PhD (2007) in Religious Studies at Marquette University under the direction of (now Archbishop) Alexander Golitzin. Between 2007 and 2020, he was Assistant and then Associate Professor of Theology at Duquesne University, in Pittsburgh, where he worked in the areas of Early Christian Studies and Reception History of the Bible. In 2010 he was ordained a priest in the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese (AOCANA) and served as the pastor of St Anthony Orthodox Church in Butler, PA (2010-2020). He was elevated to the rank of archpriest on 28 September 2023, by the hand of His Eminence, Metropolitan Saba (AOCANA).

23 February 2024 © AIOCS

For another essay by Father Bogdan Bucur published at AIOCS, see this.

Please support our not-for-profit ministry (ABN 76649025141)

For donations, please go to https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/aiocsnet or contact us at info@aiocs.net