A Yearly Celebration on 20 July

Alina Victoria Paraschiv

Believers’ devotion towards Saint Elijah is obvious in a series of glass-painted icons produced in Transylvania’s workshops. These icons evidence the popular assimilation of the saint’s scriptural biography with local legends and beliefs. Agrarian and pastoral communities saw him as a protector endowed with divine powers for managing nature’s rhythms. As Scripture speaks of his closing and opening the skies (3 Kings 17:1; 18:45), Transylvanian peasants believed that he brought the rain in due time, keeping the hale away from the crops and safeguarding people and households from thunder strikes and fire. Even I remember something of this sort from my childhood. When I twitched at the terrible noise of the thunder during a summer storm, my grandmother would comfort me saying, “It’s Saint Elijah, who snaps his whip and drives his chariot through the clouds!” This popular perception has ancient roots, originating in the Roman mythological image of Jupiter mastering the thunderbolts while driving his fiery chariot in the sky.

The scriptural motif of Saint Elijah being taken up to heaven (4 Kings 2:11) is widespread in the popular art of Transylvanian glass-painted iconography, where it appears in roughly three forms. The first two icons illustrate the first pattern, the third icon represents the second pattern, while the fourth icon presents the third pattern.

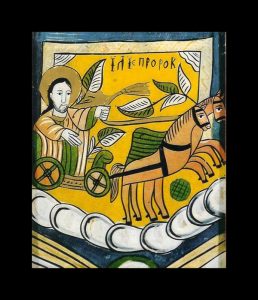

The first icon (Sebeş, the nineteenth century)

www.europeana.eu

This representation is reminiscent of the Byzantine models. It shows two events in the saint’s scriptural biography, his experience in the desert and his being taken up to heaven. Both events capture the essence of his prophetic ministry, his faith and fiery zeal. While at his prayer Israel was divinely punished with drought for idolatry, the prophet found refuge in a cave where God fed him through the intermediary of ravens. Then, upon his being taken up to heaven, he was carried away by the whirlwind in a carriage pulled by fiery horses. His falling mantle evokes the passing on of the prophetic gift unto his disciple, Saint Elisha (4 Kings 2:9-13). This second episode also alludes to the eschatological episode of Saint Elijah’s return as a forerunner of the Lord’s second coming. The composition is well-balanced, drawn by a firm hand. The ochre-golden background evokes the fiery glory in which the saint now abides.

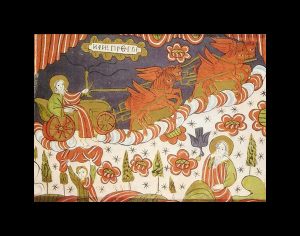

The second icon (Făgăraş, the nineteenth century)

www.icoane-vultur.ercomp.n

The composition has a strong peasant flavour. The white which covers the land could represent snow, perhaps as a sign of the saint’s power over the clime. The white land is also reminiscent of the Manichaean motif of terra lucida, “the luminous earth.” Interestingly, alongside flowers and trees, stars embellish the earth. In turn, the sky is dark and starless. This reversal—the luminous earth and the dark sky—appears to be an eschatological projection, anticipating the new heaven and new earth of Revelation 21:1. The apocalyptic dimension of this representation is obvious.

The third icon (Şcheii Braşovului/Fundata, possibly the nineteenth century)

www.europeana.eu

This representation seems to copy a mural composition. As elements of novelty, it shows an angel hovering over the clouds and a peasant ploughing his land. This peasant is identified as Adam. His presence evokes a widespread Bogomil story about the paradisal ancestors where Saint Elijah also is a character.

The fourth icon (Nicula, the nineteenth century)

www.icoane-vultur.ercomp.n

This composition reduces the ascension motif to its basic message. It shows Saint Elijah driving his fiery chariot in the sky. The golden background and the plant motifs suggest a paradisal scenery.

May we be protected, through Saint Elijah’s prayers!

[Trans. from Romanian and adapt. by Doru Costache]

19 July 2020 © AIOCS