Father Matta al-Miskīn’s on Participation in the Divine Life in Commentary on the Gospel of St John

Part One: Creation, Fall, Incarnation

by Wagdy Samir

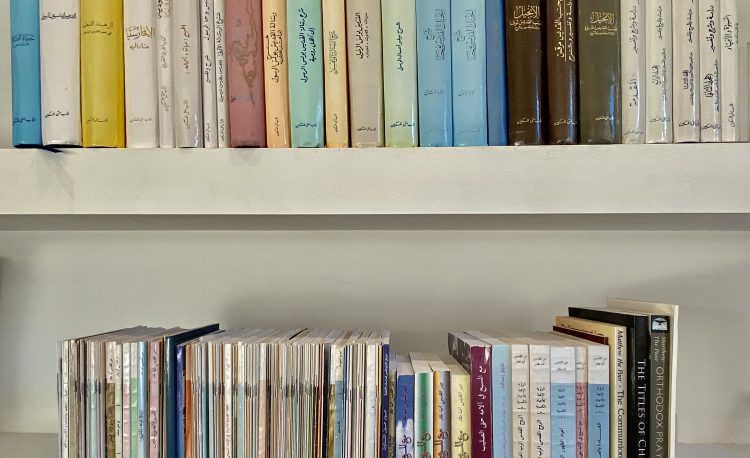

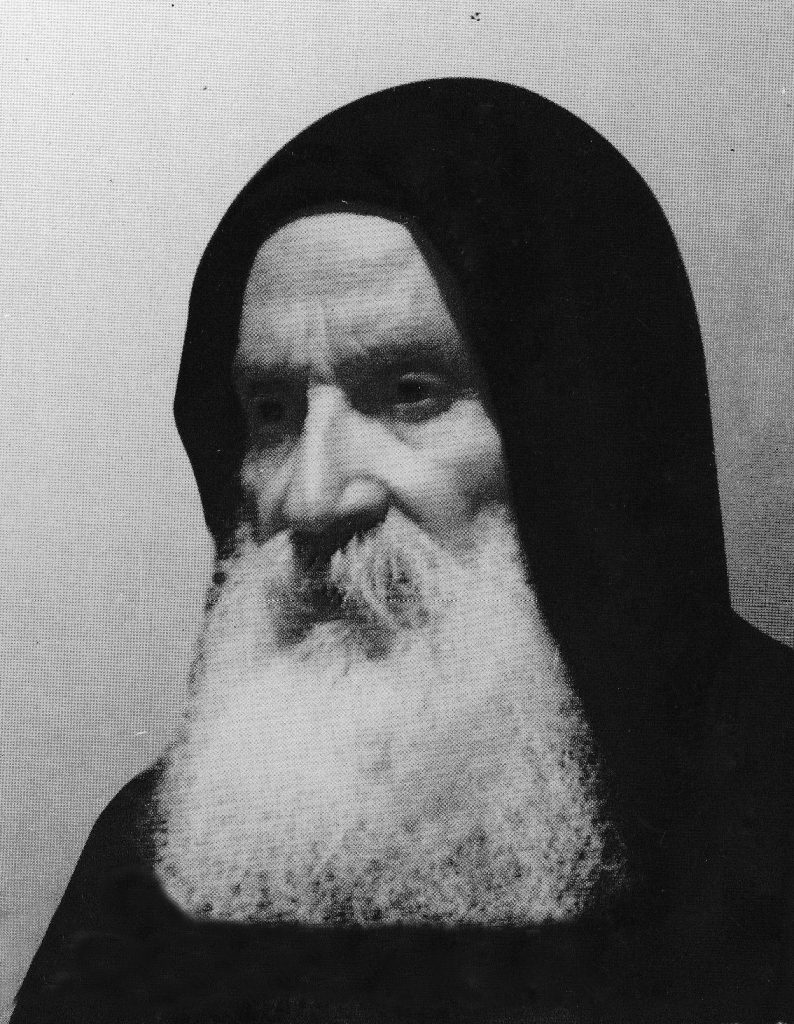

The focus of this article is on Fr Matta al-Miskīn’s Commentary on the Gospel of St John, written in Arabic between 1989 and 1990. He produced a tripartite volume, an Introduction, Volume I, and Volume II, amounting to more than 1800 pages. This article addresses the three volumes from the viewpoint of divine participation. Hereafter, I refer to the three volumes as follows: Commentary Introduction: pages, Commentary I: pages, and Commentary II: pages.

The focus of this article is on Fr Matta al-Miskīn’s Commentary on the Gospel of St John, written in Arabic between 1989 and 1990. He produced a tripartite volume, an Introduction, Volume I, and Volume II, amounting to more than 1800 pages. This article addresses the three volumes from the viewpoint of divine participation. Hereafter, I refer to the three volumes as follows: Commentary Introduction: pages, Commentary I: pages, and Commentary II: pages.

It is impossible to summarise, here, Father Matta’s Commentary. In what follows, I refer only to his views of humankind’s divine participation espoused therein.

For him, as for the patristic tradition, humankind’s creation in the image and likeness of God is the necessary backdrop for interpreting John’s Gospel. The divine image denotes God’s intention of creating humankind for eternal life. The image has become “operative” when God breathed life into Adam’s nostrils, inaugurating humankind’s orientation towards the creator, immortality, and holiness. As such, Adam was expected to progress in holiness and truth, to realise his divine destiny. Father Matta adds that the “natural being” was created so that it might progress into a “spiritual being,” without which Adam could not have known, loved, and listened to God. Humankind, indeed, possesses a capability that surpasses all created aptitudes, leading to attainments above nature. Father Matta adds that God made humankind capable of “a spiritual realisation that transcends the limits of time and creation, to [end by] knowing God in his being, attributes, and works” (Commentary Introduction:194). By this capacity for knowing God, humankind can progress towards union with the divine.

Together with many early Christian and medieval theologians, Father Matta believes that the incarnation was part of God’s eternal plan regarding the creation. He points out that John 1:1 declares that the Logos was working towards humankind’s salvation before time and creation. He further construes the connection between the Word and creation through John 1:4 (in him was life and life was the light of the people). Here, “life” is eternal life revealed to humankind that it might live forever in God’s presence. Likewise, “light” denotes the knowledge of God. Both “life” and “light” were hidden in the Word from all eternity, being revealed through his incarnation.

Taken together, these images entail that our immortality entails “progressing” towards the divine union. Humankind’s primordial orientation towards God does not mean union nor, therefore, immortality; union and immortality are accomplished only through the new birth from above, in Christ. In Adam, humankind was meant to partake of the “tree of life” (the Word) and in order to live forever. Separation and estrangement from God occurred when humankind willingly deprived itself of the tree of life by disobeying the commandment. Its progress towards deification was thus interrupted. Against this dramatic backdrop, God’s love towards the world was revealed through the incarnation, a mystery which the Word harboured within himself from the beginning. However, given God’s eternal plan, despite humankind’s interruption of this plan, union with God remains humankind’s calling, reactivated and accomplished in Christ as Word incarnate. As we read, “the greatest sign Christ fulfilled in his life—that extends in eternity—is his incarnation, thereby the Logos became the bearer of all the mysteries of God and creation, and all of God’s eternal thoughts, bodily” (Commentary Introduction:187).

But before I turn to the salvation wrought though the Word’s incarnation, I must point out that the creation/paradise narratives cannot be understood without considering the fall and its consequences for humankind. Father Matta depicts the fall as Adam’s autonomous desire to attain knowledge without having to discern between good and evil. In the absence of discernment and wisdom, the resulting knowledge was false: humankind was overcome by fear, especially the fear of death. Deceived, in Adam humankind was exiled from God’s presence, needing to be born from above in order to reenter God’s presence. Not all was lost. Irrespective of the depth of sin, the Spirit of God never “fully” departed from humankind, but was, as it were, dimmed. And given this dimness, together with all the other outcomes of sin, the incarnation had to take the form of salvation before showing its preordained sanctifying purposes—or rather before providing humankind with the proper means for attaining union with God and thus immortality. As Father Matta explains,

The union of the divinity with the humanity in an inseparable unity is the foundation of the union in the opposite direction, humankind’s union with God. However, while the former, the divine descent did not cause the Son to lose his divinity, the latter, human ascension, necessitates that humankind—the servant—lose its old self in order to receive the excellence of adoption to God (Commentary Introduction:176).

Father Matta insists on the single subjectivity of the person of Christ—after the union, one cannot divide the person (hypostasis) of the Word incarnate into two. Without this premise, humankind’s union with God is impossible, and humankind’s return to God is unachievable. Furthermore, union with Christ conditions humankind’s union with God. Indeed, those who receive the incarnate Word receive kinship with God by adoption and grace, becoming “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). Christ glorifies human nature to the extent that, as the new creation, it is called “Spirit-bearer,” “Christ-bearer,” and even “God-bearer.” In this light, it becomes manifest that the ultimate aim of the incarnation is humankind’s union with God.

What makes this gift possible is the presence of the whole of humanity in Christ. To Father Matta, the title “Son of Man” denotes that Christ includes within himself the whole of humanity, and presents it to the Father. Christ’s humanity is—without loss of its uniqueness and concreteness—representative of the whole of humankind. In descending from heaven, the Son of Man gathered in his person and his body the whole of humanity. Through his ascension to heaven with his body, the whole of humanity is in him and dwells with him. The notion of the recapitulation of all of humanity in Christ saturates Father Matta’s theology of divine participation.

The incarnation, therefore, reveals and accomplishes the relationship between humankind and God. It is a mystery whose manifestation culminates with Christ’s death, resurrection, and ascension. On the cross, Christ bore within himself and nailed humankind’s sin. In so doing, he restored “the filiation of humankind to God.” Furthermore, through union with Christ in the resurrection, humankind is “raised through and in him,” Christ becoming the “life of everyone.” Moreover, Christ ascending to the Father restored humankind’s full relationship with God and opened to it the horizon of immortality.

Thus, for Father Matta, God’s eternal orientation towards humankind and humankind’s primordial orientation towards God are revealed and intersect in the incarnation and the activity of Christ, Word of God incarnate, crucified, resurrected, and ascended. This is the central topic of Saint John’s Gospel.

Dr Wagdy Samir (PhD mathematics; PhD candidate in theology at the Sydney College of Divinity) is the AIOCS Director for Orthodox Studies

22 August 2021 © AIOCS

Check out Part Two of this essay

AIOCS LTD is a not-for-profit charitable organisation that promotes the study of Orthodox Christianity, Eastern and Oriental, in Australia

For donations, please go to https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/aiocsnet or contact us at info@aiocs.net