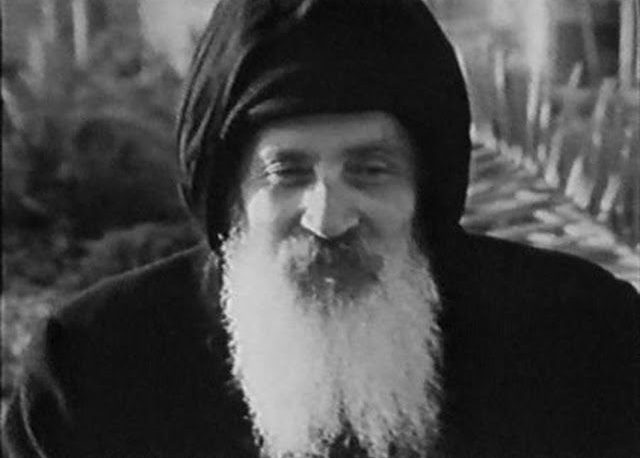

Father Matta al-Miskīn’s on Participation in the Divine Life in Commentary on the Gospel of St John

Part Two: The Spirit and the Sacraments

by Wagdy Samir

In addition to his intense christocentrism, Father Matta also refers to the Holy Spirit’s role in his account of humankind’s union with God. In fact, the primary goal of salvation is the reacquisition of the Spirit lost through sin. Manifestly, Father Matta’s theology of redemption is thoroughly christological and deeply pneumatological. Three aspects are worth highlighting here.

First, the connection between Christ and the Spirit. As Christ is the truth, so is the Spirit who reveals and guides the disciples to know the Father and the Son. Accordingly, when Christ is in the disciples, so is the Spirit in them. Thus, the Spirit indwells humankind so that it (humankind) realises its adoption with Christ in God and is “continuously filled to all the fullness of God.” He adds that it is Christ who “exceedingly filled our spirits with (his) Spirit” so that humankind might rise above its nature and be “joined to God (in Christ).” Receiving the Holy Spirit after Christ’s ascension (John 16:7-11) seals the disciples’ “unseen union with and in Christ.”

Second, Father Matta also stresses that the Spirit’s indwelling in the disciples extends to the whole church. The Spirit’s inhabiting the disciples (John 14:17) inaugurates an “eternal union” with them as the “firstfruits” of the church. The disciples, obviously, recapitulate the church, and their experience anticipates that of the church in its entirety.

Related, third, the interplay between the Spirit and the sacraments of baptism and eucharist in the context of union with God. Commenting on John 4:23 (worshipping God in spirit and truth), Father Matta points to believers being born again from the Spirit through baptism, by which they are sanctified. Likewise, in the eucharist communicants receive, together with the flesh of the incarnate Word of God, his Spirit, since the Holy Spirit cannot be separated from Christ.

The three aspects denote that, for Father Matta, Christ sent his Spirit that he (the Spirit) might indwell all of humanity. Through divine indwelling, humankind is able to receive what is above its nature that it might attain to union with God.

It is in this light that we must understand Father Matta’s theological view of baptism and the eucharist in the context of participating in the divine life. He observes that Saint John did not discuss baptism and the eucharist from a ritual perspective; instead, he emphasised the efficacy of the sacraments in sanctifying believers.

In commenting on Christ’s baptism, Father Matta argues that Christ himself did not need to be baptised, nor did he need the Spirit to descend upon him at the River Jordan, since he is always one with the Father and the Spirit. Thus, in Saint John’s Gospel the event at the Jordan was revelatory, not salvific. He argues that the “remaining” of the Spirit upon Christ was a “sign” to the Baptist to recognise the Lord. Furthermore, the anointing Christ received in the Jordan was “for the beginning of his ministry, rather than for his being filled” by the Spirit. However, Father Matta’s interpretation of Christ’s baptism does not ignore the sanctification humankind receives in baptism, a notion he expanded upon in his other writings. What made our sanctification possible is our being recapitulated in Christ; in the Lord, we received the Spirit as a sanctifying power.

On a related note, Father Matta adds that Christ’s conversation with Nicodemus reveals that baptism, the birth from water and the Spirit, is a creative action. Through baptism, humankind receives a heavenly birth certificate sealed by the Spirit and the Father in the form of the Son’s image. He hints at the link between the trinitarian aspect of humankind’s creation (the Genesis narrative) and humankind’s recreation through baptism. Thus, Commentary affirms God’s plan to unite humankind to himself in baptism.

Corresponding to Father Matta’s baptismal theology is his eucharistic theology. For him, the eucharistic union of the communicant with Christ is the most excellent means of attaining fellowship with the Son of Man. Even though humankind did not eat of the “tree of life” as it was initially supposed to do, God sent the “bread of life” to humankind in the fullness of time. The “bread of life” is the eucharistic flesh of Christ. Christ’s real presence in the eucharist is central to Father Matta’s understanding of humankind’s union with God. Christ’s words, “food indeed” and “drink indeed,” denote the real presence of the single person of the Word of God incarnate in the eucharist. Accordingly, the “flesh of Christ” given on the holy tables contains all of Christ’s divine, sanctifying power. To deny the real presence of Christ in the eucharist or to understand eucharistic participation merely in moral and memorial terms amounts to diminishing Christ’s incarnation and sacrifice on the cross. Through eucharistic participation, communicants share in Christ’s sufferings, death, and resurrection—“God did not save the world through the spoken word, but rather through sacrificing the Word incarnate” (Commentary I:448, 458-459).

The real presence of Christ in the eucharist enables the union of communicants with the mystical flesh of Christ. Referring to Ephesians 5:30, Father Matta points out that Christ permeates the communicants’ flesh and blood with his own flesh and blood that he might live in them through eucharistic communion. The eucharistic abiding is reciprocal and personal; Christ is in each communicant, and each communicant is in Christ. Thus, for Father Matta, the eucharist is not merely a blessing, but a means to attain union with God.

It is noteworthy that Father Matta’s sacramental theology does not refer to the divine initiative alone. Our real birth from above and the union between Christ and communicants, although predicated on the creative work of the Spirit, still require a human response. The interplay between the divine activity and the human response is patent in Commentary. The divine activity precedes the human response. However, this does neither exclude nor diminish humankind’s free will in accepting the faith (John 6:64). Believers must “willingly accept death” if they are to attain holiness. Their mystical “death” receives its reality from Christ’s death for the sake of all believers. As a result, those united to Christ by being born again through the water and the Spirit and through eucharistic participation, overcome perishability.

A final note on Father Matta’s theology of union with God is in order. He does not let the readers’ minds wonder about the similarity and the dissimilarity between the hypostatic union as the reality of Christ, the Word incarnate, and humankind’s union with God. The Son is the “true light,” whereas humankind “partakes” of his light. The Son “is the only-begotten,” and his sonship is “by nature and in essence,” whereas humankind’s filiation to God is “by adoption.” That said, humankind’s union with God is real, with God bestowing sanctification and the seal of the Spirit that believers may become living members of his only-begotten Son, “from his flesh and bones” (Ephesians 5:30). Humankind’s mystical union with God in the here and now is but a prepayment for what is to be revealed at the final resurrection, when the darkened body of today is changed in the likeness of Christ’s glorious body (Philippians 3:21). Thus, Father Matta observes the distinction between what is by nature and what is through grace, or by adoption, in an eschatological perspective.

Throughout Commentary, Father Matta makes clear that humankind can reach holiness. This is perhaps most clearly expressed in his very first book, Orthodox Prayer Life, where he says:

Is it possible for humankind, in this earthly existence, to reach a state of utter holiness and to put on a new nature? The answer encompasses the very essence of Christianity. Christ came into the world, sacrificed his body, and shed his blood. He vouchsafed his union with us through the mystery of faith and the work of the Holy Spirit. This was done that we might attain through him total holiness. Such holiness qualifies us not only to see God but also to be united and live with him (Orthodox Prayer Life 84).

In this light, Father Matta maintains that God created humankind that it might have life with him and in him. The Commentary depicts various facets of the relationship between God and humankind. God, in his Son, showed himself to humankind. The Word transfigured creation with a transcendent sanctifying power, deifying it. In the Commentary, Father Matta locates humankind within the divine sphere of holiness at every corner. His views on union with God or participation in the divine life should be evaluated within the structure and concepts outlined above.

Dr Wagdy Samir (PhD mathematics; PhD candidate in theology at the Sydney College of Divinity) is the AIOCS Director for Orthodox Studies

29 August 2021 © AIOCS

Check out Part One of this essay

AIOCS LTD is a not-for-profit charitable organisation that promotes the study of Orthodox Christianity, Eastern and Oriental, in Australia

For donations, please go to https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/aiocsnet or contact us at info@aiocs.net