by The Seeker

The divine liturgy is the local community of the kingdom gathered together in partnership with God and sharing in the divinised humanity of Christ. It is clear that it is a local community from the first section of the liturgy—at Saint Gregory’s called, after the ancient custom, synaxis, “the gathering”—and in language like “this assembly.” The opening line makes clear that it is the community of the kingdom: “blessed is the kingdom of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, now and ever and to the ages of ages.” To pronounce the kingdom blessed is to suggest that we are desirous to be under the rule of its king, and just so to open ourselves up to its rule.

The divine liturgy is the local community of the kingdom gathered together in partnership with God and sharing in the divinised humanity of Christ. It is clear that it is a local community from the first section of the liturgy—at Saint Gregory’s called, after the ancient custom, synaxis, “the gathering”—and in language like “this assembly.” The opening line makes clear that it is the community of the kingdom: “blessed is the kingdom of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, now and ever and to the ages of ages.” To pronounce the kingdom blessed is to suggest that we are desirous to be under the rule of its king, and just so to open ourselves up to its rule.

This openness to the rule of God is the precondition for everything else that happens in the liturgy, because everything that happens in the liturgy—prayer and ritual action—is possible only as synergy. This is seen powerfully in the liturgy’s affirmation that it is God who has “given us these prayers to offer together and in harmony, and have promised to grant the requests of even two or three who join together in your name.” The community uses donated language to ask the God who donated it to act, on the basis of God’s own promises.

Here Jesus’ own words, said right before teaching his disciples how to pray, are significant: “your Father knows what you need before you ask him” (Matthew 6:8). Why pray if the Father knows what we need? The only possible answer is that he wants us to ask, wants us to come to him, in some limited way to partner with him. The liturgy is the people of kingdom coming before the king to praise, petition and adore him in prayer.

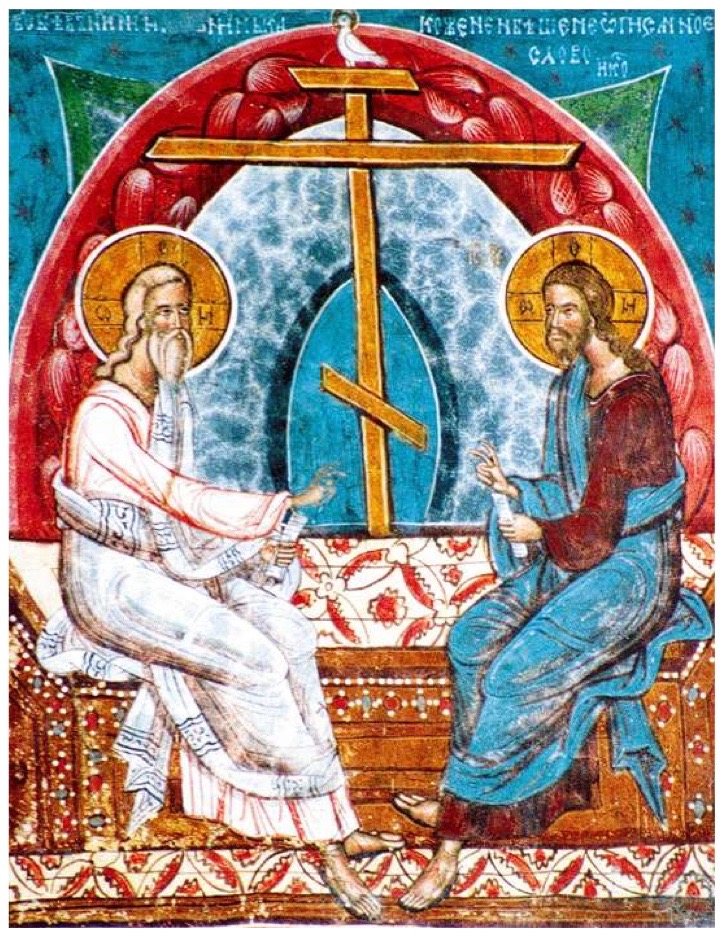

Ritual actions have the same dual aspect. And this insight can be generalised: as Vladimir Lossky says, the church is “a theandric organism, or, more exactly, a created nature inseparably united to God in the hypostasis of the Son, a being which has—as He has—two natures, two wills and two operations which are at once inseparable and yet distinct” (Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, Ch. 9). The liturgy is a partnership with God because the church in its very essence is a partnership with God.

The divinised humanity of Christ is experienced in the most pronounced form in the eucharist. Here, as William Cavanaugh (Being Consumed) points out, we do not consume the eucharist so much as we are consumed by it: the eucharist rejects our identification of ourselves with our individualistic wills, and begins to grant us personhood.

The Orthodoxy I see in the liturgy, then, is communal, synergistic, and unitive with God. It is experiential rather than rationalistic: it is centred in prayer and sacraments. And these prayers imply the need for action, with an eye on both the believing community and the world. There is, then, a sense in which the Orthodoxy of the liturgy takes us from (“blessed be the kingdom”), locates us in (“for the peace of the whole world”), and gives us back to the world (“let us go forth in peace”). In this way, I see Orthodoxy as the communal experience of unifying partnership with God for the purposes of God’s mission into the world.

The Seeker is a person interested in Orthodox Christianity, currently undertaking catechetical initiation at Saint Gregory the Theologian’s Orthodox Mission, Mona Vale NSW Australia

17 September 2021 © AIOCS

AIOCS LTD is a not-for-profit charitable organisation that promotes the study of Orthodox Christianity, Eastern and Oriental, in Australia

For donations, please go to https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/aiocsnet or contact us at info@aiocs.net