Forgetfulness of wisdom and identity seems to be the dominant of contemporary societies, especially those whose rhythms draw on the modern obsession with “what’s new,” with recent things. The knowledge-gathering culture of such societies does not help either, as new data piles up on top of older information, information which most times ends in the pit of oblivion before having been processed and learnt from. No wonder we end up forgetting many things, including our own identity.

Traditional societies, with their oral culture, living memory, and wisdom-gathering processes fare much better, but not us, information-oriented cultures. As we are overwhelmed by the amount of data we collect, the meaning and the connection of things elude us. Christians in general and Orthodox Christians in particular have not escaped this trap, traditional though some of us might claim to be. Clogged with the information we have gathered in history, and having forgotten the traditional processes of discerning wisdom, we have ended up misrepresenting our identity. Just think of how we understand Christianity as religion! Jesus Christ and Paul the Apostle went to the synagogues of their time—places of religious significance—to find potential listeners, and when they found, they guided the converts away from religion, to life, truth, and beauty, to the fulness of life. It should not come as a surprise that their converts called themselves “disciples,” students, and that they understood Christianity as a philosophical school, in the sense of philosophy as a way of life, not religion. For many centuries, in fact, Christian disciples understood “religion” as paganism.

In turn, contemporary Christians drag the people away from life and give them religion, with all its problems, which become increasingly obvious with the time passing. Just think of the human cost of murderous religious wars—taken either literally or figuratively—from the unbearable spectacle of Christian disunity to hatred for everything different, and from the hatred of Orthodox against Orthodox to the religiously sanctioned genocide of the Ukrainian people under the pretext of a myth. Become religion, Christianity, including Orthodox Christianity, has severed its connection with life and things—misrepresenting even the sense of religion, the way most religions do. As Basarab Nicolescu reminds us, religion means “that which binds things again,” not that which separates (Basarab Nicolescu, From Modernity to Cosmodernity: Science, Culture, and Spirituality (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2014) 14).

If there is something Christians, generally, and Orthodox Christians in particular, need to address with utmost urgency, that is our identity—an identity we misunderstand, if we have not altogether forgotten. For Christianity, especially Orthodox Christianity, is not a religion, and it should not behave as one, isolationist, intolerant, and murderous in the name of ideology and out of thirst for power.

Accordingly, I call this perception into question. My own research shows that, originally, as disciples of the Teacher, Christians considered Christianity a school (Doru Costache, ‘The Teacher and His School: Philosophical Representations of Jesus and Christianity’ in The Impact of Jesus of Nazareth: Historical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspectives, vol. 2: Social and Pastoral Studies, ed. Peter G. Bolt and James R. Harrison, CGAR Series 2 (Macquarie Park: SCD Press, 2021) 227-251)—as Pierre Hadot would have it, one that trains people for life (Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault, trans. Michael Chase (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995) 107). There are many elements within Christ’s Gospel that support this view, and the same goes for the available ecclesial evidence, whether written or chanted or painted.

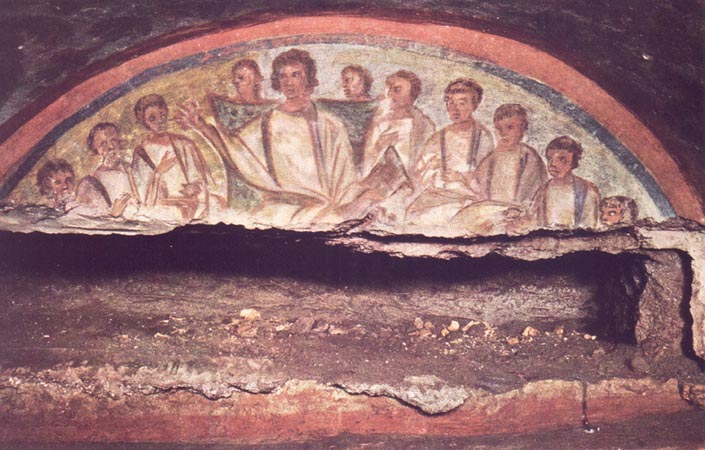

Jesus as Philosopher at the Mystical Supper. Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome, second century

The Christian phenomenon, including its Orthodox iteration, was never meant to be reduced to the status of a religion, whose ritual obscures all other aspects (Frances M. Young, ‘Christian Teaching’ in The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, ed. Frances M. Young, Lewis Ayres, and Andrew Louth (Cambridge University Press, 2004) 91–104, esp. 91). True, Christianity has emulated various religious traditions in history, from which it has borrowed a range of elements, including ritual, and has even innovated in matters religious. But, in so doing, it has utilised religious channels for the purposes of communicating Christian wisdom to religious audiences, not for dismissing wisdom and for growing oblivious of its own identity. In time, unfortunately, the religious aspect has become prevalent, bringing Christianity as a school of life almost to extinction. This is the truth we must realise and the problem we must address.

Against this backdrop, and apart from the need for Christianity to renew awareness of its origins and identity, Nicolescu’s concept of “transreligious attitude” is an excellent tool for grasping the Christian phenomenon. As the author describes it (Nicolescu, From Modernity to Cosmodernity 15), this attitude corresponds to

that which links beings and things and, in consequence, induces in the very depths of the human being an absolute respect for others, to whom he or she is linked by their sharing a common life on one and the same Earth.

This, precisely, is what Jesus suggests when he points out his intention to fulfil the law and the prophets, not to abolish them (Matthew 5:17). And knowing Jesus as the Logos of all existence, law, wisdom, and prophecy, the early Christians took his words as a promise to all cultures to become mature. It is this common denominator, namely, seeking maturity, that allowed the early Christians to assess and to welcome the contributions of other cultures as intrinsically Christian. Their attitude was transcultural and transreligious. Recent research has alerted us about the nonreligious nature of early Christianity. The time has come for us, Christians, including Orthodox Christians, to interpret these findings, and Nicolescu’s concept of “transreligious attitude” is extremely helpful to that end.

Echoing Constantin Noica’s conviction that, so far, homo christianus is the highest human achievement (Constantin Noica, De caelo: Încercare în jurul cunoaşterii şi individului (București: Humanitas, 1993) 153), Nicolescu understands Orthodox spirituality, for example represented by Saint John Climacus’ Ladder of Divine Ascent, as mapping human spiritual evolution (Nicolescu, From Modernity to Cosmodernity 205). Elsewhere, he refers to the icon as the fullest—insofar as transfigured—image of nature (Basarab Nicolescu, Transdisciplinaritatea: Manifest (Iași: Polirom, 1999) 33–34, 78–79). From this vantage point, I would say, Christianity constitutes a framework for human development, for cultivating the noble life, for realising humanity’s full potential (Doru Costache, ‘Being, Well-being, Being for Ever: Creation’s Existential Trajectory in Patristic Tradition’ in Well-being, Personal Wholeness and the Social Fabric, ed. Doru Costache, Darren Cronshaw, and James Harrison (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017) 55–87). As such, Christianity, in transreligious and transcultural fashion, appreciates the views, the values, and the victories other cultures have achieved in their quest for spiritual maturity (Nicolescu, From Modernity to Cosmodernity 16). This perception of Christianity finds abundant confirmation in its early and medieval history, times when Christians viewed themselves as disciples of a philosophical school. It is to this wisdom that we must return in order to retrieve Christianity’s forgotten identity. Basarab Nicolescu’s concept of “transreligious attitude” points us in the right direction.

Acknowledgment “Beyond Religion: (Orthodox) Christianity in Transdisciplinary Perspective” was offered as a paper for Basarab Nicolescu 80: Anniversary Symposium. Romanian Academy, 25-26 March 2022 (online)

26 March 2022 © AIOCS

AIOCS LTD is a not-for-profit charitable organisation that promotes the study of Orthodox Christianity, Eastern and Oriental, in Australia

For donations, please go to https://www.paypal.com/paypalme/aiocsnet or contact us at info@aiocs.net