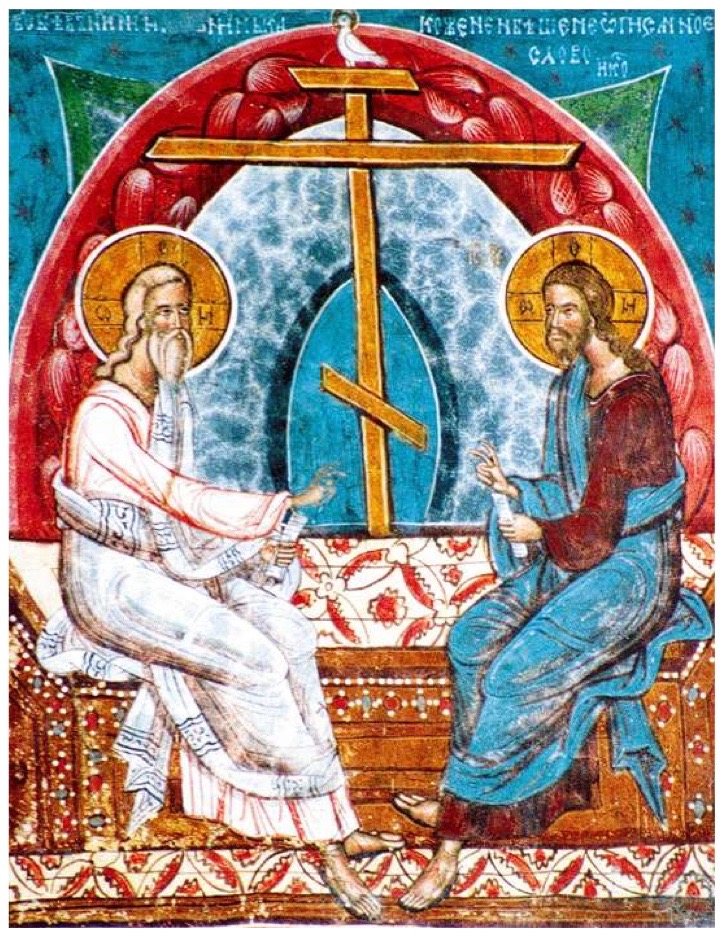

The icon reproduced on this page, painted by an anonymous artist in the 15th century, is in fact a mural depiction to be found at Moldovița monastery, Romania. This icon of the Holy Trinity offers glimpses of numerous mysteries, recapitulating the whole divine economy for our sakes, or for the restitution of our wholeness (one of the meanings of the word ‘salvation’ in the Classical Greek). I what follows, I share a few thoughts, which come to mind when I gaze upon its beauty.

The Holy Trinity, whose revelation is the content of the feasts of Theophany (Epiphany) and Pentecost, is uniquely represented here in a colloquial posture. The Father, represented as the Ancient of Days, and the Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, face one another as if talking, and both bless the holy cross in concord – a summary of the entire economy, accomplished through the Lamb of God’s sacrifice. On the top of the cross rests the Dove, in a clear suggestion of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit as the culminating outcome of the crucifixion. Many times, Fr Dumitru Stăniloae insisted on the idea behind this tremendous image of the divine council, or colloquium, to which the whole of creation is called, with or without mentioning the famous fresco. Not without reason an exegete of his work, Maciej Bielawski, OSB, penetratingly remarked that Fr Stăniloae’s legacy can be summarised along these lines: “in the beginning there was a dialogue, and at the endless end there will be another dialogue.”

Every time I contemplate this icon, it appears to me as a pointer to the divine blueprint of creation, which begins with the pretemporal moment when the Son of God and true God turned his face toward the Father as Christ and Logos of creation (John 1:1), saying: “let us make the human being according to our image and according to likeness” (Genesis 1:26 LXX). This is the moment when the Son of God as Logos of creation put on the “form of God” (Philippians 2:6), becoming the Prototype of our fashioning (for we are called to become in the image of God’s Son; Romans 8:29) and in so doing anticipating his profound kenosis in the “form of a servant” (Philippians 2:7).

The mystery of the cross features at the very centre, as an encryption of the entire plan, like in St Maximus’ vision of the whole creation established on the Lord’s sacrifice, which in turn exegetes the meaning and purpose of creation… τὰ φαινόμενα πάντα δεῖται σταυροῦ (“all visible beings are in need of the cross”)… And thus, the divine epiphany announces at once the origins of everything and the climax of the whole plan for the creation, the parameters within which we are called to understand the purest and the universally demiurgic act of crucifixion, the Lord’s whole-burnt offering. Furthermore, this icon shows that far from being an accident in history Christ’s crucifixion reiterates “in the fullness of time” his original and foundational sacrifice – of the Lamb upon whose life the life of the world is built (Revelation 13:8). Nothing exists without being founded on this sacrificial bedrock…

I take this opportunity to add that I am worried about the new wave of iconoclastic denial of the iconographical representation of the Father as an old man. According to the promoters of this new iconoclastic trend, any icon of the Father is illegitimate, given that the Father never took flesh… How silly this is. The Holy Spirit never took flesh and we still represent him/her/it as a dove and as tongues of fire; and we do this given his/her/its epiphany in such forms. In fact, the epiphany/revelation/manifestation is a significant presupposition of icon-making – if not the ultimate presupposition, the Logos’ incarnation being the culmination of all revelations. And if the revelation of a person is what makes an icon possible, then the representation of the Father as an old man is legitimate. I am thinking here of the canonical epiphany of the Father as the Ancient of Days in Daniel 7:9-10,13-4, toward whom walks the Son of Man, a prophetic revelation which might have very well served as a pretext for the Moldovița fresco. In addition, unlike the Holy Trinity’s angelic representations, our icon makes an important differentiation between the unincarnated Father, depicted in a white, transparent attire free of material density, and the incarnated Son, clothed not only in the flesh, but also in the heavier colours of the creation.

Last, but not least, this icon speaks to me of a different yet not an unrelated level of reality. It seems to recast upon the mystery of the Trinity the light of another mystery, namely, spiritual guidance. The persons in the icon, the Father and the Son, in the love of the Spirit, reflect the spiritual elder and the spiritual child whose rapport is founded on the Spirit. The elder teaching the disciple under the wings of divine inspiration – thus forwarding the legacy, signified by the identical scrolls held by both Father and Son in the icon – is prefigured by this archetypal image of the eternal council, or colloquium, where the Father entrusts the Son the accomplishment of salvific economy. Considered from a different angle, this icon reveals the trinitarian archetype of spiritual guidance. In so doing, it illustrates the divine and human mystery of colloquial existence.

Acknowledgment. In it original form, the text was published in The Greek Australian Vema, July 2011, p. 9, here presented in a thoroughly revised version.

30 May 2018 © AIOCS