by Alina Victoria Paraschiv

Glass iconography, or the folk art of painting sacred images on the reverse of glass plates, developed in Transylvania during the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Out of a profound spiritual necessity stemming from their faith, the Romanian peasants of those times ornamented the eastern wall of their homes by hanging there glass icons, which they lovingly adorned with embroidered towels.. Thus would they signal the presence of the Holy Trinity, of the Incarnate Lord, of the Lord’s Mother, and the saints. So arrayed, the interior of a peasant home pointed to the conviction that the believers were not only dwellers of their own homes; they were also members of God’s household. This original folk art was not based on the canons of Byzantine iconography. It has drawn on the religious imagination of people nurtured by an oral Christian culture. And it has likewise depended on the talent of the artists, the creative manner in which they embodied their own perception and experience of the events. In anticipation of the Birth of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, herein I present four such creations, sharing with you aspects of how Transylvanian peasants of a century and a half ago rendered in images the inner beauty of the festival.

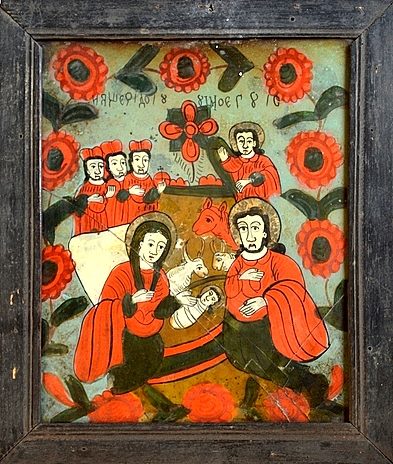

The first icon. Produced in Gherla. Beginning of the twentieth century. The Romanian inscription in Cyrillic alphabet contains misspellings. The absence of the Bethlehem cave betrays a simplified, non-Byzantine rendition of the event. Located this side of the manger, the observer becomes a participant in the mystery of the Lord’s birth. If by any chance s/he misses the actual topic, the witnesses, the Lord’s Mother and Joseph point to Christ. The hands of the Mother are folded in prayer. Leaning on his staff, Joseph points towards the humble one who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. The dark-coloured swaddling clothes anticipate the sacrifice and death of the Lord on the cross. The cosmic scenery, rendered in cerulean blue, seems to come into focus through the ox and the donkey, which breathe upon the newborn their warm breath. The nativity star is highly stylised to look like a flower or maybe the tree of life. Red roses frame the composition, against the background of white (snowy?) fields, borrowed from Slovakian glass paintings. These decorative frames were usually drawn when the original icon was smaller than the glass plate on which it was copied. However, the white fields and the red roses are not just a compositional artifice; they are in harmony with the fundamental message of the icon. The red flowers, possibly hinting at the blood of the cross, are undoubtedly a reference to the beauty of paradise. Through the birth of Christ, the door of paradise is reopened. Despite the clumsiness of the drawing, which ignores anatomy, the figures of the Lord’s Mother and Saint Jospeh express with shy and sober awe the significance of the event. The primitivism of this art did not take away from the mission of the painter, who was fully aware of what s/he conveyed by way of this icon.

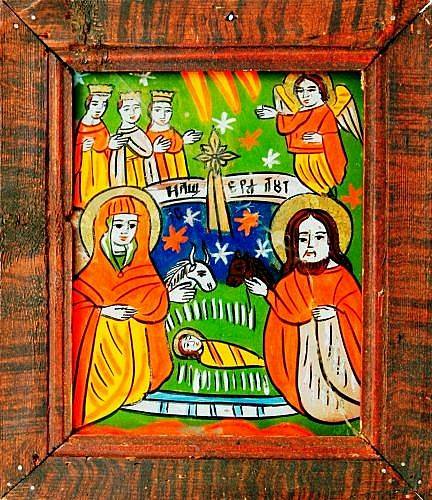

The second icon. Produced in Gherla. Beginning of the twentieth century. The Romanian inscription in Cyrillic alphabet contains misspellings. Although the cave is still missing, this icon follows a closer model to the canons of Byzantine iconography. The magi bear gifts marked by crosses. The angel points towards the star. The star is rendered again like a flower or the tree of life. The usual floral frame, betraying a synthesis of cultural influences, appears however in chromatic accord with the floral star. The Lord’s Mother and Jospeh kneel in adoration next to the manger where the pure (mark the white, resurrectional swaddling clothes) newborn Lord lays. The puzzlement of Joseph echoes Byzantine iconography. Also of Byzantine influence seems to be the concern of the Mother bent towards the child, as though talking to him.

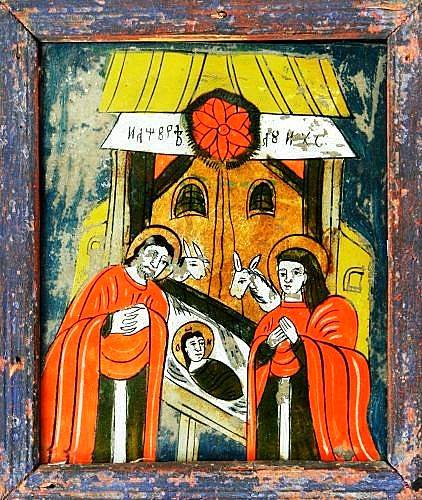

The third icon. An icon found at Nicula. The second half of the nineteenth century. The composition is based on different patterns from the Gherla exemplars. It is likely that it was produced elsewhere. The building in the background reminds of the architecture of the famous gates of peasant properties in Maramureş (Transylvania’s northern parts). Recent research has proven the existence of a centre that produced glass icons in Maramureş about the same time as the workshop of Nicula. The traditional Bethlehem cave becomes a household annex. An immense star shines on the roof, whose resplendent rays bathe Jesus. Gentle and inquisitive, Joseph bends towards the newborn, who again is represented in the dark colours of the crucifixion and the tomb. In turn, the Lord’s Mother stands up in meditation, her hands being joined together in prayerful contemplation. Both witnesses appear in hieratic posture, but uprightness shows also their shyness before the Lord.

The fourth icon. Unknown workshop. The first half of the nineteenth century. The change in the background colour brings to the fore the various regions of the visual narrative. Particularities of a mountain landscape are obvious, the highlands alternating with the lowlands, both areas communing in the vibrant green of a springtime meadow (paradisal scenery?). The various regions are clearly demarcated by way of horizontal lines; one such space is that of the inscription. The green background and the starry sky characterise the art of the painters of Ţara Bârsei (Germ. Burzenland, southeastern Transylvania). The cave and the star of Bethlehem feature within a new context, that of local geography. The characters are emotionless, possibly because one should focus only on the newborn, not on the witnesses. Situated at the same distance from the royal newborn (mark the golden swaddling clothes), kneeling in adoration, the Lord’s Mother and Joseph show not only to the magi (represented as kings), but to the entire visible and invisible creation, whom all should worship, Jesus Christ, the newborn king. The same message is conveyed by the central vertical line formed by the threesolar rays referring to the Holy Trinity, the golden star and its rays, and the royal newborn. [Trans. and adapt. D. Costache]

Icons found at www.europeana.eu

Originally posted at Saint Gregory the Theologian Mission.

The author’s previous essays on glass icons can be accessed here and here.