by Doru Costache

In the Orthodox tradition, the Great Week begins with Saturday of Lazarus and ends with Holy Saturday. These Saturdays are like the brackets of the mystery, both focusing on the mystery of resurrection. Saturday of Lazarus anticipates the rise of the Lord. Holy Saturday celebrates the rise of the Lord. The Week is called Great not only because of its significance; it also is because of its length, eight days. It marks the transition between the catastrophic (overthrowing) time of Lent, when the weeks count seven days, beginning Sunday and ending Saturday, and when the morning services are celebrated at night while the evening services in the morning, to the eschatological time of Pascha, when the weeks count eight days, beginning Sunday and ending Sunday, and when the morning services are celebrated in the morning while the evening services in the evening. The Great Week is the time of great change. The best way to make sense of the change is by looking at the scriptural readings of the week. From the immense amount of readings, in what follows I ponder only those given during the liturgies of Saint Basil and Saint John.

Saturday of Lazarus

A day before Palm Sunday

Hebrews 12:28–29; 13:1–8. John 11:1–45. Anticipating the events of his own death and resurrection, to reassure his disciples Christ brought back to life his friend, Lazarus. The difference between the two happenings is obvious: whereas Christ resurrected by his own power, Lazarus depended on his Lord. But, today, more important is the common message of the two readings, that is, that all who believe in Christ become partakers of a new life and that they should live accordingly. They transcend death regardless of their biological condition. Indeed, they might be physically dead, yet they are in the presence of the Lord, or they might be physically alive, yet without being separated from him. Nevertheless, the Christian experience is not oneway. It does not consist only in the divine activity or the grace God bestows on the believers. Christian life is resurrectional, entailing a continuous striving to live as renewed people, walking in the footsteps of Christ. The apostolic passage details the fundamentals of the renewed life, showing what Christians must undertake in order to be worthy of their name, as their spiritual leaders did—the practice of gratitude, the practice of compassion, the practice of pure life, trusting in the Lord. They must walk as long as there is light, living as children of light and children of the day (Ephesians 5:8; 1 Thessalonians 5:5). They become Lazarus, “God has helped,” by living as though already resurrected.

Palm Sunday

A week before Easter

Philippians 4:4–9. John 12:1–18. The compatriots of the Lord misrepresented his entry in Jerusalem as a claim to earthly power. Christians ought to know better and not expect from him what he never promised to offer, namely, worldly kingdoms, property, and ruling authority. Christ’s bodily line was indeed that of King David, but he never called himself Son of David as he never expressed desire to ascend to the throne. Symbolically riding on a donkey, he illustrated the principles of peace and humility. So did he enter Jerusalem, the city of peace, as king of peace who imparts peace and joy to the souls of his disciples. This is what we are to understand. This is the message of the festival—the city where the Lord wishes to enter is our own heart (Revelation 3:20). The best way to grasp this message is by considering it through the eyes of the author known as Saint Macarius the Great, who contemplated the Chariot of Glory in Ezekiel 1 as a revelation of Christ dwelling in the hearts of his people as though on a throne of glory (Spiritual Homilies 1.1–2). Therefore, we must make ourselves available to him by reshaping our existence, by humbly making room for him to lay his head upon our lives (see Luke 8:58), so that through his grace our minds and hearts can become peaceful, enlightened, and full of joy.

The Mystical Supper

Thursday before Easter

1 Corinthians 11:23–32. Matthew 26:2–20; John 13:3–17; Matthew 26:21–39; Luke 22:43–44; Matthew 26:40–27:2. The practice of the Church, from the very beginning to date, to celebrate the participation of the believers in the sacrificed body and blood of Christ, is associated with thanksgiving and joy. The eucharistic sharing in the body and blood of the Lord is for salvation and eternal life. But not so was in the beginning, at the first eucharistic celebration of the disciples. Worry and fear clouded the supper when the Lord established the new covenant with his people. They knew from him that the time has come for him to die. Their emotions were consequently at the surface, shifting from the firm decision to die with him to cowardice and betrayal. The sorry farce of the religious tribunal is of no consequence here. Merely another example of the murderous drive of religion. What matters is what the Lord taught his disciples then, that the new alliance was an act of togetherness, an act of fellowship with God and fellow believers, an act of communal participation in the divine life. Such is the way of Christian life, and this is what we celebrate, not religious prescriptions, but the law of love. This is why what ultimately matters is for the disciples to examine their conscience and so participate in the body and blood of Christ—only if they did nothing to cause sorrow to Christ’s little sisters and brothers.

The Paschal Vigil

Saturday before Easter

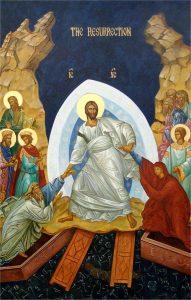

Romans 6:3–11. Matthew 28:1–20. Believing in Christ crucified and risen is the beginning of a transformative journey—a mystical death and resurrection with the Lord whose vehicle and symbol is their baptism. Through faith and baptism (Mark 16:16), people find salvation by being one with Christ, but in order to earn their perfection they must live a resurrectional life. In short, this is a matter of reconsidering their priorities and changing orientation. Abandoning their sinful habits, they must turn to God and live a God-centred life. They must keep the teachings of the Lord, foremost his commandment concerning love for one another (John 15:12–13) as the supreme good. This is the gift of the crucified and risen Lord for his disciples: the opportunity to renew and to live meaningful lives. The path they must walk is arduous, doubts could overwhelm them at times, but the Lord is with them to the end.

20 April 2019 © AIOCS